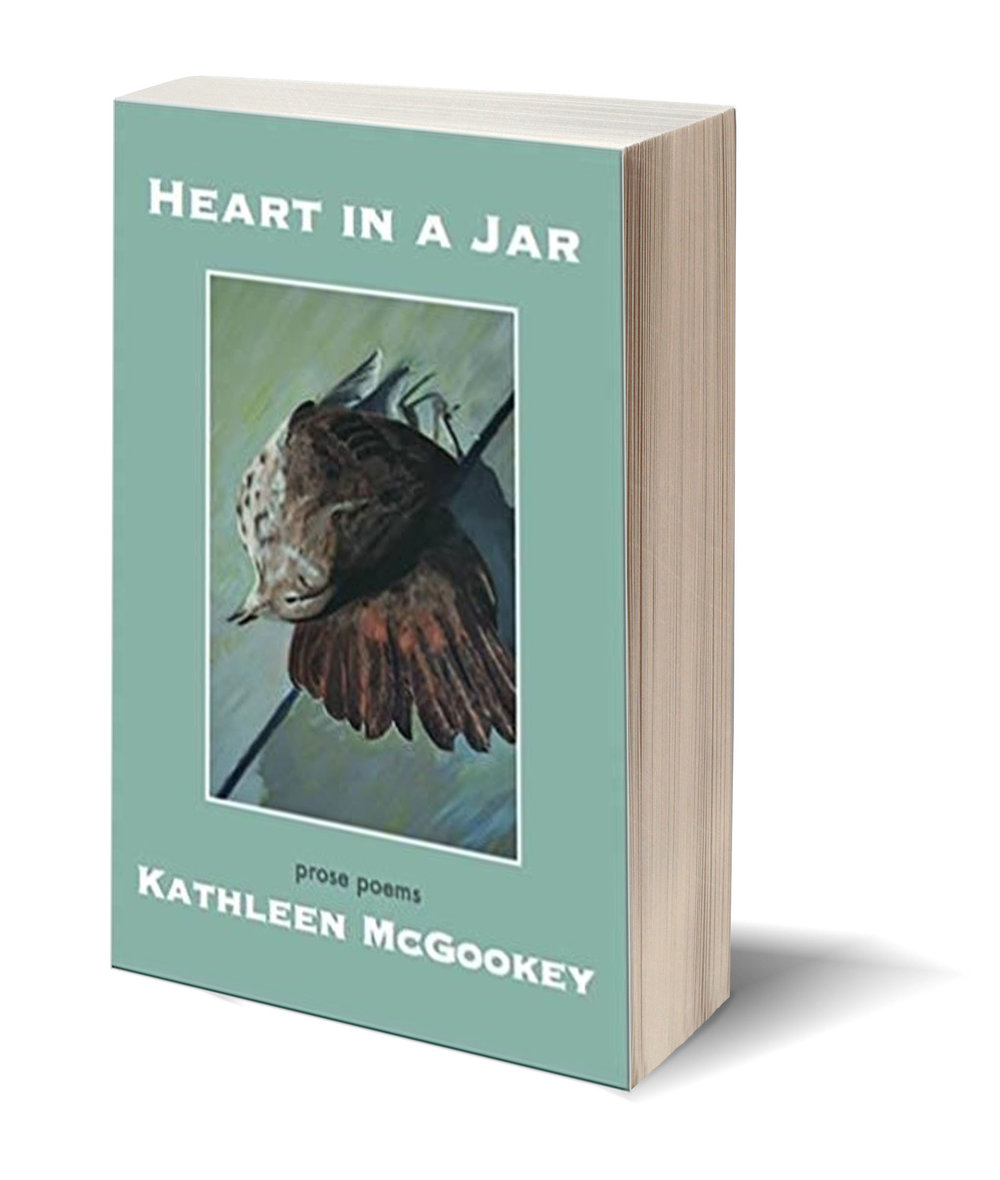

Heart in a JarBy Kathleen McGookey

White Pine Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Janeen Pergrin Rastall

Imagine entering paintings by Dorthea Tanning or Frida Kahlo. If you transcribed the pain and beauty in those works into poetry, it would read like Kathleen McGookey's Heart in a Jar. These prose poems illustrate a journey through grief and parenthood. Angels, animal spirits, and ghosts abound. Childhood memories mingle with dreams. Daily events become fanciful like the bus ride that ends in a forest full of dangling mannequins or the son who dons bird wings instead of play clothes. The playroom, the yard, the school become exotic, but Death, the narrator's companion and pen pal, is always near. As the reader navigates a minefield describing motherhood and the loss of a parent, the talismans of birth are juxtaposed with images of life's fragility.

There is bargaining in the collection's opening poem, "Dear Death,": "can't you see we're busy riding bikes in the sun? . . . Let's pretend you forget all about us." There are also wry attempts to manipulate Death. In "It's March, Death," the narrator admits, "Talking to you feeds my illusion of control."

McGookey explores the depths of grief, yet avoids sentimentality with her skillful use of magical realism and humor. "Nothing sings or swings or swims in me." Her narrator lives in a pond dug by Death; she navigates it in an ivy-covered life raft. "In here, it is always night," she notes, "The rooster sleeps all the time." The book is not a dirge. Comic relief comes through unexpected subject matter. You will never look at a rejection letter the same way, for example, after reading "Ordinary Objects, Extraordinary Emotions," a museum's rejection letter in response to the donation of a dead mother's items. The committee regrets that the submitter did not send the "best" items. They would have considered the dead mother's prom dress and "perfect plaster reproductions of her feet" for a Day of the Dead exhibit.

McGookey looks with a calm eye at the difficult or grotesque and finds grace and kinship. Nothing is spared her steady gaze. There is a skunk in the dollhouse and a possum skull in the field. She shows us an un-Disneyfied version of childhood. Mothers are not perfect. A doll is mistaken for a daughter. A mother pulls a child out of a flower garden like a weed. "Thank You for Your Question" gives us images of earwax and juxtaposes preschoolers' tussles with the serenity of rocking a baby at 4:00 a.m. When a stray cat kills songbirds in the back yard in "Death, Now Where's the Skinny Stray," McGookey's speaker prepares a box to take it to the shelter and tells her kids it might find a home, knowing the cat will likely die. In fewer than a hundred words, McGookey deftly examines the complexities of what and whom we choose to protect and the consequences of those choices.

Ultimately, Heart in a Jar is a survival guide. In "Like His Heart in a Jar," a boy shows his love for the narrator by placing a dead lab cat in her locker. She does not flinch. She examines the gift of Death with curiosity, but does not give her heart away. She demands answers from Death or at least that she be asked a new question. Death can no longer ask for her heart. She refuses to reside in mourning. Death becomes like a series of gifts from an unwanted suitor.

When sorrow swallows the narrator in "At the School Costume Parade," the poem dazzles with details of costumed children, a stumbling ladybug, and a sticky werewolf. We are simultaneously inside the chaos of the classroom and the grieving mind of the narrator. Here, McGookey reveals the secret to survival. It is writing—the poetry on library receipts, on any bit of paper—that rescues the narrator. Her scraps escape through a hole in Death's pocket and end up in a sparrow's nest. They are Dorothy's shredded message sent to Oz via "Tornado Machine." Death can no longer keep her and it ends as a neighbor who can visit, but cannot stay.

McGookey is a sneaky poet. She packs each prose poem with lyricism and gorgeous images like "a field lit by dandelions" or the "last brief bit of birdsong." I did not expect to have lines from prose poems lingering in my mind long after finishing the book. McGookey is gifted at posing remarkable questions. The narrator asks Death what it will remember her by and what it thinks of Spring on a scale of 1 to 10. She wonders when Grief will miss her too. Finally, the book answers the question where a parent's love for a child goes after death. That love lives on in the slips of paper from the pockets of angels that fall into the river and that fall as well into McGookey's collection. In brief prose poems, she gives us a deeply-felt look at an adult child's love for a parent and a mother's love for her children. You will want to hold tightly this heart she has offered. Keep it close by.