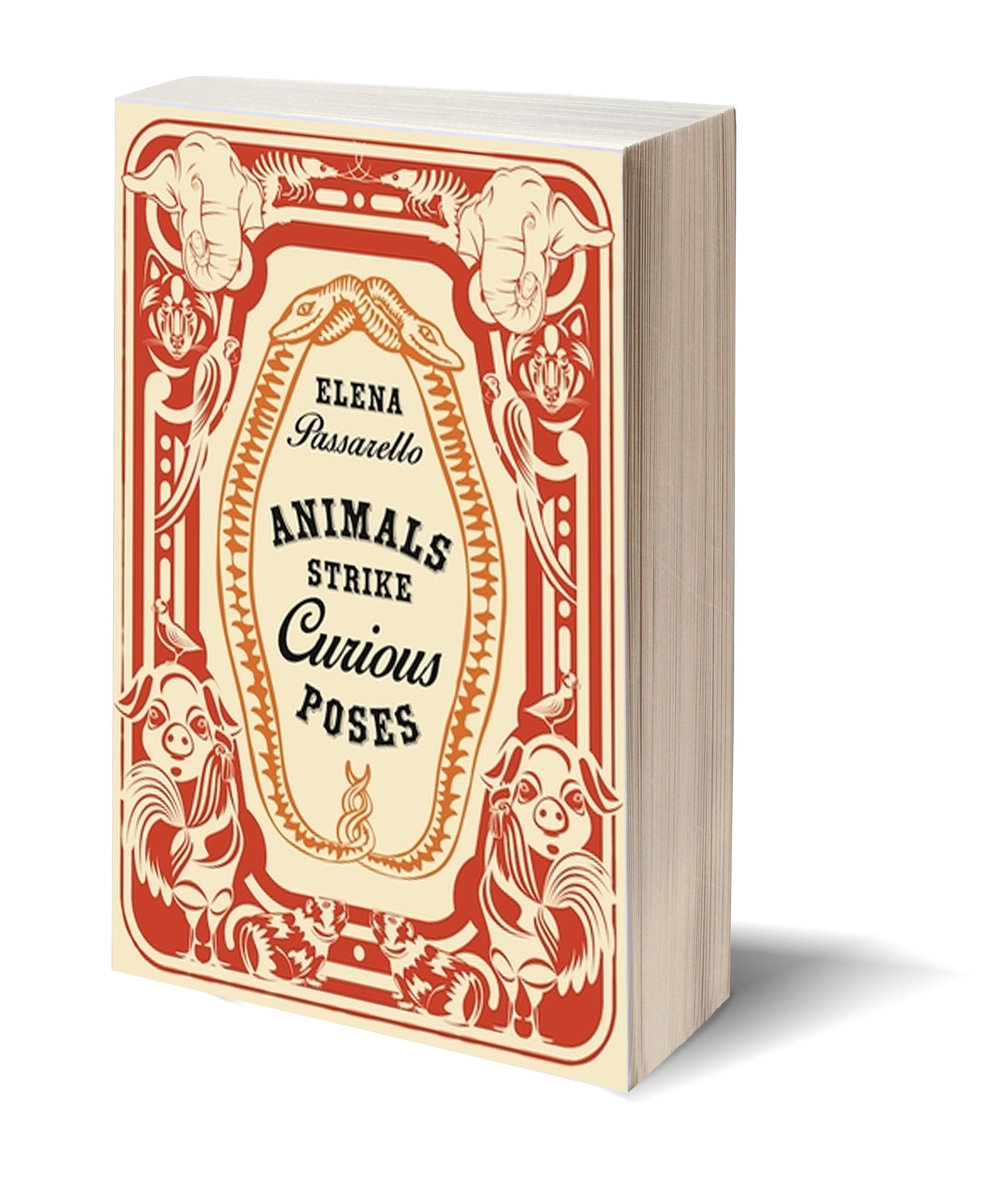

Animals Strike Curious PosesBy Elena Passarello

Sarabande |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Daniel Rousseau

Imagine that it is the fourteenth century. You are a British royal, and have never left Europe. One day, as you scan your family's bookshelves, you discover a thick, red leather bestiary. The hand painted animals on the pages are unlike anything you've ever seen: cats the size of men, birds with gold and turquoise plumes, and long tongued dragons. The book's illustrator has embellished newfound animals, which European explorers have spotted in the Far East, so that they resemble mythological creatures—colorful beasts which carry your imagination away from its isolated perch, and into an exotic world.

Elena Passarello's essay collection, Animals Strike Curious Poses, is organized as a bestiary. The book is split into seventeen sections, which move in chronological order, each section considering a famous animal. In line with historical bestiaries, the book's creatures are as real as Koko—a gorilla who understands two thousand spoken English words—and as fanciful as Albrecht Dürer's Rhinoceros: a steel plated, two-horned behemoth drawn from hearsay. While the reader will likely recognize some of the animals in the book—like Cecil the murdered lion, and Arabella the astronaut spider—Passarello's dive into history, fantasy, and cultural reality will prod the mind to imagine creatures, and humanity, in new ways.

Passarello's essays, which vary in length from four to twenty-eight pages, represent a number of unique forms. For example: the section on Koko is written in the gorilla's sign language vocabulary. Of this essay, Passarello writes, "I've not strayed from that documented lexicon, I've tried to evoke the syntactical pairs that myriad sources report the gorilla employing." As Passarello uses Koko's dialect to tell a slapstick joke, the reader feels the gorilla's rhythm, and empathizes with her.

Also unique is Passarello's section about a cat, titled "Jeoffry," which is written as a poem. The author discusses her approach to the section, "I learned that the most famous cat poem in English is actually a fragment. Apparently, Christopher Smart's Jubilate Agno . . . has several lost sections." Using the open door of Smart's unfinished work, Passarello considers the cat. In a sea of essays, the poem is a curious and rare animal; not unlike a unicorn surrounded by horses.

The strongest moments of Passarello's work come through her considerations of the relationship between humans and animals. In "Vogel Staar," she discusses a starling that belonged to Mozart. The composer would whistle a tune to the bird, then the bird, whose brain was not bound to traditional human standards, would return the song with unpredictable sharps and flats; an intricate interpretation that blew Mozart away. Passarello writes, "It is difficult to imagine a more priceless moment: one of the greatest thinkers in history bonding with a bird brain." The author's tale of Mozart and his bobbing starling shows that a symbiotic relationship between man and beast is possible.

The longest essay in the collection, "Jumbo II," chronicles the history of captive elephants in America. The work tells of circus elephants being chained, poisoned, run into by trains, and electrocuted. Passarello uses these tragedies to highlight one of the book's core themes: the fine line between use and abuse.

In the essay "Lancelot," Passarello's body enters the book for the first time. As a first grader, she sits beneath a circus tent and watches a goat-turned-unicorn parade in front of the bleachers. A veterinary surgeon, who patented "a method for growing unicorns," had grafted the goat's horns to the center of its head. The circus invented the animal. Of her childhood perception of the facsimile unicorn, Passarello writes, "Most of the animal world held for me this incorrect magic, which spurned me toward an impasse—an inability to note the contextual divide between the animals that shared our world and the ones that were invented to please me." It is here that the modern world is opened up as a malleable bestiary, where we will allow animals to entertain us, so long as they fit into our imaginations. The we more we name, train, and modify animals, the more they reflect our fears and desires. In this way, the divide between man and beast is thinning.

Elena Passarello's poetic prose, keen observations, and wise considerations illuminate the unique qualities, and universal truths in her subjects. The work is quick, funny, informative and at times humbling. To open Animals Strike Curious Poses is to unleash a breathtaking bestiary.