Belle Turnbull: On the Life and Work of an American MasterBy David Rothman and Jeffery Villines, editors

Pleiades Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Mitchell R. McInnis

Belle Turnbull's poetry is filled with a rhapsody familiar to folks in the Rocky Mountain West. It's found in the awe-driven brushstrokes of Thomas Moran and Thomas Cole attempting to capture the ineffable sensory rush of standing inside the Yellowstone's Grand Canyon. And it is in the corpuscle of emotions inside every visitor to the Rocky Mountains who's considered abandoning their fettered lives for the peace, freedom, and mythological simplicity of the American West. And while this mythological language works amazingly well in paintings and movies, the ineffable, peaceful, and free are not usually the stuff of good poetry. Born and raised in Colorado, Turnbull understood not only the language of poetry, she understood and was fluent in the language underlying the mythology of the West. She understood what so many have traveled in search of, only to find despair while re-finding the shackles of their previous lives. In short, she understood an epic landscape does not an epic individual make. Belle Turnbull: On the Life and Work of an American Master, assembled via the able stewardship of David Rothman and Jeffrey Villines, grants readers passport to a conversation that's been taking place in Colorado for some time, with the deliberative hope that it will become a national conversation.

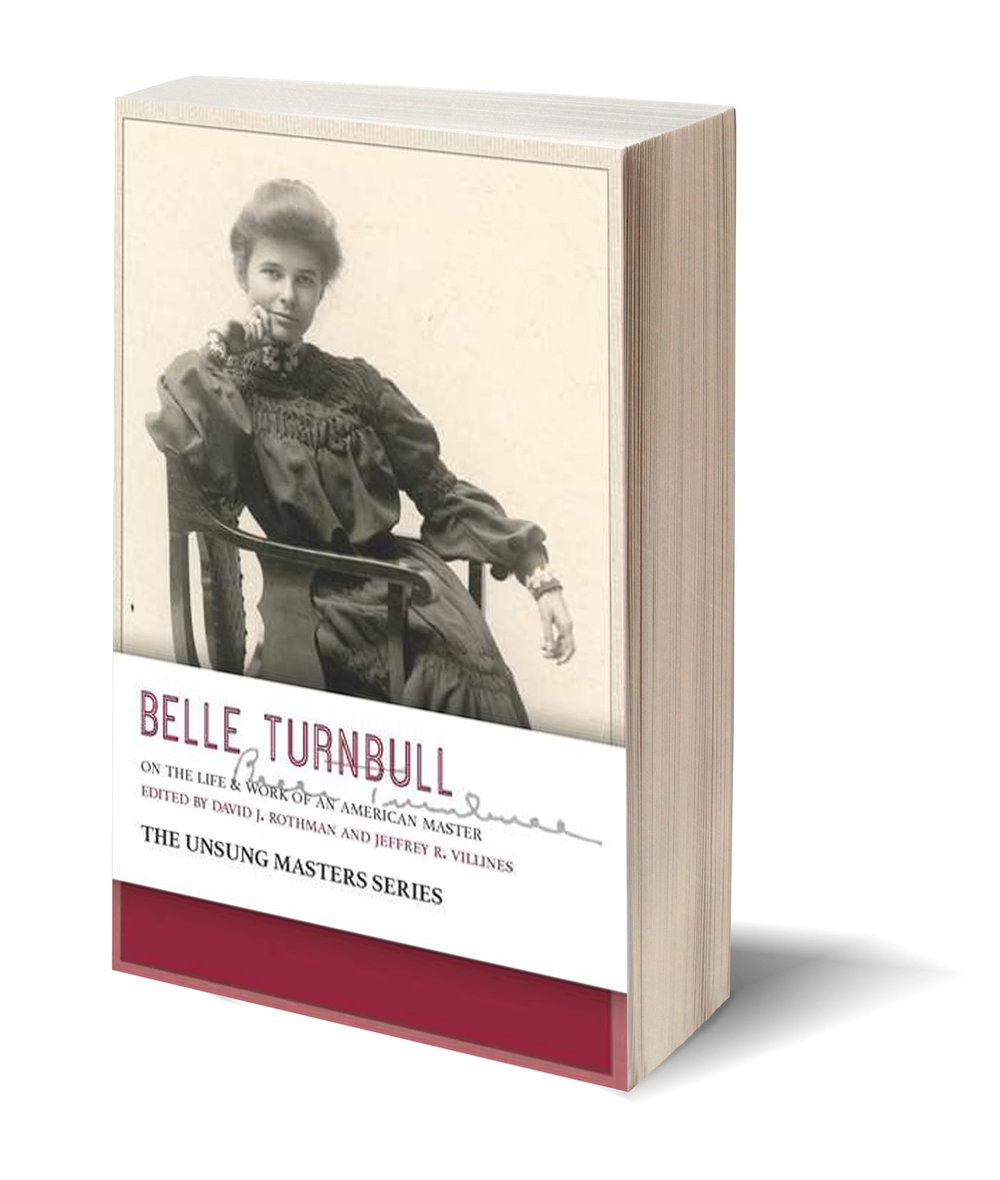

Shattering myths and highlighting struggles is more of poetry's crucible, and Turnbull knew it. Raised in Colorado Springs and graduating from the very high school where her father was principal, she earned her way into Vassar College. Upon graduation, she taught for five years in upstate New York, the locale of her birth, before returning to Colorado Springs to teach at her old high school. One of the few photos of Turnbull is of her "in her senior frock" from 1903. In it, she looks like the portraits of English romantic poet Letitia Elizabeth Landon or like America's first poet, Anne Bradstreet. Her striking gaze is intensified by the thoughtful placement of her right hand in a romantic thinker's pose; her self-possession bespeaks her ambition and belies any stereotypes of women being dainty and decorative as doilies. As Turnbull wrote decades later in her poem "Mountain Women,": "God love these mountain women anyway, / [. . . .] Not to say they're fair / Or sleek with oils, for woodsmoke in the hair / And sagebrush on the fingers every day / Are toughening perfumes, and the sunstreams flay / Too dainty flesh. But what remains is rare, / Like mountain honey to the mountain bear."

Turnbull won what she described as the "coveted" Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize in 1938 from Poetry magazine for her collection "The Tenmile Range." And with that prize came national recognition. In his introductory essay, Rothman scales boldly onto a precarious ledge (since we're talking about mountains, why not . . .): "[Turnbull's] Tenmile Range, which runs past Breckenridge, Colorado, should figure as significantly in our collective imagination as Shelley's Mt. Blanc [sic]." Lest he be in the strange business of comparing mountain ranges—which is more a job for the Breckenridge visitors bureau than for a poetry scholar—we are to take Rothman's statement as a comparison of poets. More precisely, it is a comparison of Turnbull's prize-winning work with Percy Bysshe Shelley's ode "Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni."

If you climb miles above the Flint Creek Valley, in western Montana, you can visit a ghost town called Granite. Granite is just southeast of Philipsburg, a tiny town made famous by the poet Richard Hugo in "Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg." Standing inside the mouth of the largest of defunct mines that pockmark this fancifully rich mountain (once known as "The Silver Queen" by miners), staring out over the green valley to the snow-capped Continental Divide, one understands two of Turnbull's unforgettable lines: "Never along that range is ease" (a line she repeats in multiple poems) and "Things are warped that are too near heaven." To stand miles above that picturesque valley at the site of so much immigrant toil is to feel the weariness and pain that underlies the mythology of the West. At that oxygen-starved elevation, one is urged to ask the too near heavens why and how such ethereal beauty inspires such wanton greed and violence in men. It is the earthly debunking of Eden to imagine the sleepless miners working shift after shift in the noise and indenture of the mines, their own bodies used like drill bits and pick-axe points to burrow inside the awe-inspiring mountains. For silver, for gold. Merely. Things are indeed warped too near heaven, and for anyone who comprehends the murky sluice flowing beneath, too dark to be stained by human blood, there is never ease. And this is just the horrible irony for the miners, who sought redemption from their crippling poverty. It doesn't even begin to address the massacre of Native Americans and the raping of their lands that were their religion and way of life. As Cormac McCarthy so aptly entitled it, this region is a blood meridian. And yet, it remains indescribably, painfully beautiful and undeniably alluring.

Such darkness does not obsess Turnbull's poetry, nor the transformations necessary to overcome such darkness, bringing it to light. But it is the obsession of Shelley's "Mont Blanc." Turnbull's "Tenmile Range" reaches out like the plain-clothed angel of the Bethesda Fountain, touching gently, forgivingly. Shelley's "Mont Blanc" is a Nietzschean transformation, the work of a Dionysian artist struggling deeply with his own mythmaking abilities. While Turnbull offers clear-eyed observation, Shelley engages in a deliberative grappling with the mountain's "solemn power as player in the poet's transfiguration, realizing, as Nietzsche wrote in the Birth of Tragedy, "The lyric poet's images are nothing but the poet himself." Turnbull's "Tenmile" feels more oracular than transformative, more consoling than grappling. Part of this difference between these two poems, the nimble scholar might observe, is due to the authors' genders. Perhaps. (And in pure terms of literary criticism, it does distinguish between male and female textual characteristics, separate from the authors' respective genders.) But it certainly implies different poetic projects. In itself, this difference does not connote the supremacy of either project. However, a side by side reading of the two puts Rothman's comparison in the charmingly hyperbolic category. Unlike Shelley, whose ideas grapple dithyrambically with one another and his syntax, Turnbull's syntax looms and enchants, an aesthetic experience in itself. Like the visitor beholding the most majestic of peaks, there is a beatific capture by and in the moment—syllable to syllable—that is a distinguishing mark of her "Tenmile." Her work is not preoccupied with metaphysics or possessed of overarching vision en route to solving and/or illuminating her "too close to heaven" paradox. And overall, while her achievement makes her a noteworthy poet, it does not put her in the company of major poets like Shelley, Bishop, Moore, or Dickinson. What's more, she chose a local and regional subject matter during a time of internationalism. One year before Turnbull won the Monroe Prize, 1937, Picasso painted Guernica, and one year after she won, World War II started and among other redresses of the same, W.H. Auden wrote his stunning poem, "September 1, 1939." Choosing isolation rather than engagement, Turnbull took her prize money and retreated further into the mountains.

To sing the unsung is a laudable task. It is a curator's and archivist's task. An academic task. However, while academic, it smacks ecclesiastic, which is why some of the best literary revivalists—like Bloom and Sontag—sound as much like preachers as they do archivists. The scholarly essays that accompany Turnbull's work are passionate epistles of a sort, and they illuminate praiseworthy aspects of her work. But in the end, taken together as an argument for Turnbull's work to "leap the regionalist fence" as Rothman put it, they are unconvincing. In a description she wrote regarding her 1953 novel The Far Side of the Hill, Turnbull writes, "Perhaps the book differs from most other works in this field in its acceptance of the realities rather than the romance in the lives of mountain people." The very same could be said of her overall project as a writer. In fact, as a further category of consideration, Turnbull's work in "Tenmile" is a compelling example of early documentary poetry.

It is a charming eccentricity of archivists that we sometimes fall in love with delicate patterns in the dust and how they've somehow arranged themselves in whorls over the decades. And it is this mystery that beguiles and bedevils our work. Several aspects in the comparison of Turnbull and Shelley reminds of a glorious quote by Cheryl Walker: "Something inheres in women's poetry which has the force of a secret kept alive by a clandestine group." This quote seems a perfect epigram, here in the dregs of the wine, so to speak, not only for Turnbull's unique voice but for the mysteries that haunt all residents of the Rockies. To close with the poet's own words from "Mountain-Mad":

Mountains cast spells on me—

Why, because of the way

Earth-heaps lie, should I be

Choked by joy mysteriously;

Stilled or drunken-gay?

[. . . .]

Timberline, and the trees

Wind-whipped, and the sand between—

Why am I mad for these?

What dim thirst do they appease?

What filmed sense brushed clean?