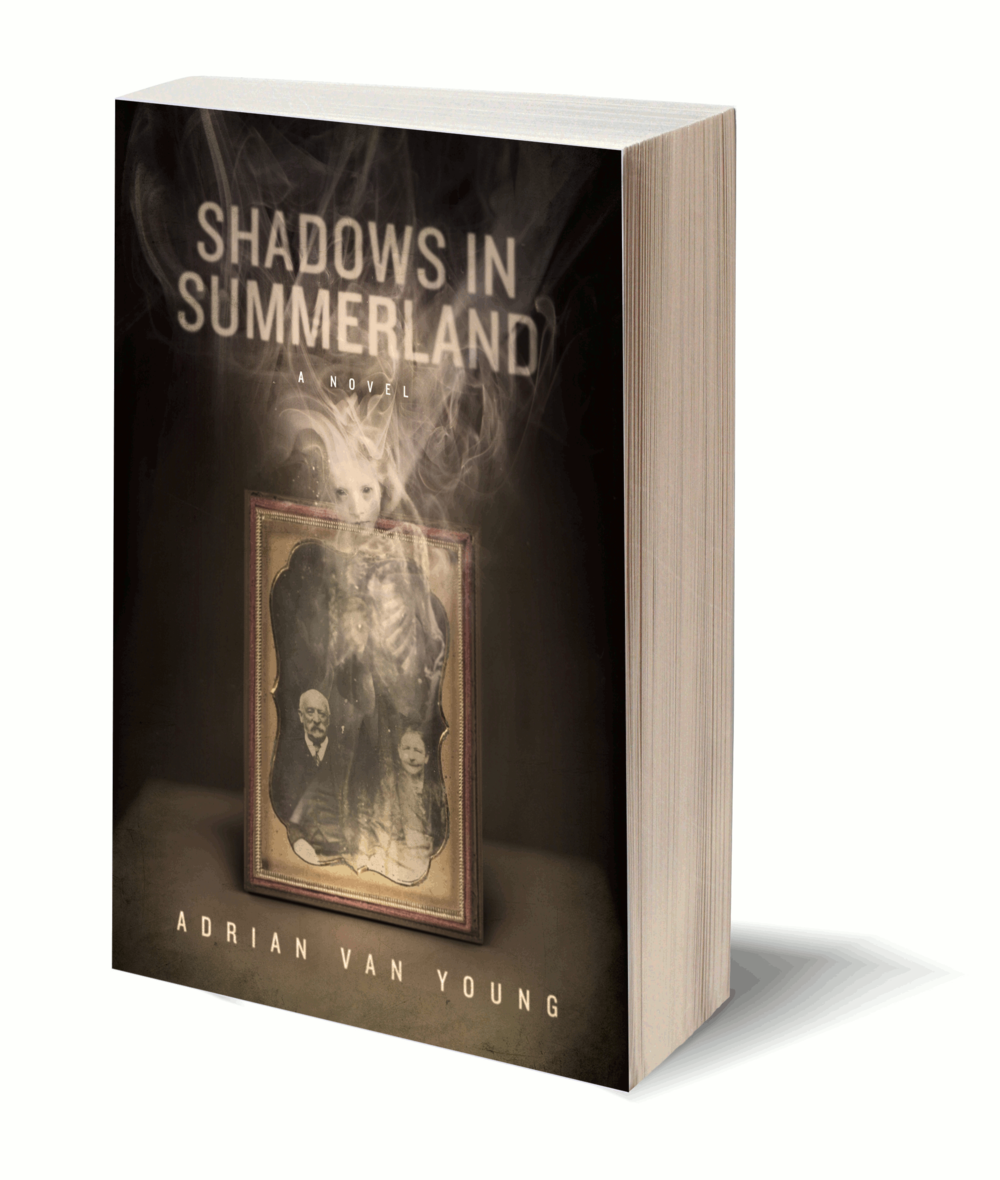

Shadows in Summerland

By Adrian Van YoungChiZine Publications |

|

|---|

March, 1850

At night they would empty the schoolhouse of children and have me up upon the stage. The stage, in this case, was a dining room table pushed against the schoolhouse wall.

They brought in coal-lanterns and lined the walls with them so nothing would escape their eyes.

The chair that I sat in on top of the table was hard and high-backed to encourage my posture. Below the chair's seat there were two pillows, on which they said to rest my feet.

The gentlemen lurked below the stage, some of them sitting and some of them standing. Certain of the standers had their hips tilted forward, their arms folded over their chests, their lips pursed.

"Permission to work the rap is granted," said a man toward the front named Shadrach Barnes.

He was shaggy-haired and blond and big—a healthy urgent country dog.

He was also a Professor at the College of Troy. He had come all the way to Roundot just to meet me.

"Permission to work the rap," he said, "has been granted the lady, assuming she's able."

He started to walk toward the head of the table, his stethoscope swinging on his chest. I let him get a foot away before I gave a single rap. He froze for a moment, assessing the sound, then began to come toward me again with new purpose. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, I rapped in succession to make him walk faster, though I'd rested the muscles in my feet before his hands could get at me.

"Do it one more time," he said.

I shook my head that I would not.

"Surely, Miss Conant can give us reason explaining why she cannot rap."

"The spirits won't speak on command," I explained. "The spirits resent such ultimatums."

"The test conditions are not right?"

"The test conditions are too much."

"The spirits are prone to stage-fright, then? The spirits are seized by performance anxiety? Why the spirits are not unlike an actress, struggling to recite her lines."

"The spirits will not humour you if you persist in making fun."

"The spirits will not or you will not?"

"The spirits respond through the medium, sir."

"Not of, but through. Not will not, but cannot. Such muddy distinctions want candor, Miss Conant."

At a loss, I shook my head.

"Confess then," said Barnes, stepping back from the table, gesturing with the hand he'd withdrawn from my foot.

The sessions went on for a week in that schoolroom. They happened long after the classes let out, somewhat past the supper hour. Shadrach Barnes was always there with the likes of the Minister Willets and others: a county judge, some aldermen, a man who'd gotten rich in coal.

Roundot was black with coal dust to the elbows. The mountains and gorges were crisscrossed with chutes. The lives of the miners, our fathers, were hard. Everyone had to do her part. I had heard of the raps from a friend of a friend, and that latter friend from the friend of another, the travelling word come down from Hydesville, courtesy of the sisters Fox.

The following sessions went much like the first. I sat there on the table on the chair beneath the pillow. People came to hear the rap, leaning in close at the top of the table. They leaned in and listened intently and long, like men listening for the sea in a shell. Some of them would smell the air, the space around my feet and legs, breathing in as much of me as decency permitted.

The men called themselves an "impartial committee"—convened in faith to break my will. Other girls who worked the rap had drawn other committees that went on for weeks but I was the first one in all of Roundot who had summoned a college professor from Troy.

Before the fourth session they took me to the basement of the school. A pack of women waited there. These were the wives of the well-to-do men heading up the inquiry. They guided me into a small anteroom that was furnished to look like a janitor's bedroom and had me lie down on a small iron bed where they started to paw beneath my clothes. They were weak pecking hens and they found nothing on me. Two of them drifted away to report. When these two returned, they conferred with the rest, too far away for me to hear.

They said to wait there on the bed. The six or so women went upstairs.

Shadrach Barnes came through the door. He was in his shirtsleeves with the stethoscope hanging. He stood in the door peering at me intently before turning around to shoot the chain. At last he sat down at the end of the bed. All of me tensed at him being so near. The bed was child-sized, almost too short to hold me, even shorter with a body perched there at the end. He readied up his stethoscope. And then, gently, he found my heart. He listened a minute, moved down to my lungs.

He drove his hand between my legs.

I gasped at the pressure and tried to fold inward, my instinct to pull, to shrink away, but the strong hand continued to grope at my lap. I made a sort of whining sound I didn't recognize as me, and again and again tried to jackknife my body against Barnes' hands, which were holding me down. I slowly retreated from what was occurring, so queer and unreal it was happening to me. I tired of kicking out my legs and lowered them onto the mattress again. And I felt a sort of warming or a summons settle in beneath the terror and the shame. The mortification of this man, touching me where no one touched, where I had scarcely touched myself, not for never wanting to but rather because I had never known how. I hated the feeling and willed it away but it was like a far off bell—at once too faint to scrutinize and too persistent dismiss.

Shadrach did not make a sound. He seemed intent that I should feel him. He worked as if it pained him to—to cause me this, to cause on me.

Sharply, he removed his hand and folded it beneath his thigh.

"I allow that you're clever," he told me abruptly. "Cleverer than most, perhaps. But sure as I sit before you now, I am every bit your match."

"You will find me out?" I said.

Shadrach Barnes did not respond.

"You will find me out," I gasped. "Yes, you, good sir, will find me out. I suppose in the meantime that I'm not to speak of what you did to me tonight?"

I waited a moment for him to respond. Instead, he stowed his instruments and rose and drew his coat about him.

"Do you like it?" he said.

"I despise it," I answered.

"Not me," he said and spread his arms to take in the bedframe, the walls. "Your new room."

"What is it that bolsters this Spiritualism?" Shadrach Barnes asked the committee of men. "It comes from out of the mouths of babes and those same babes contend it true."

He swept his arm past where I sat. I felt raw and alone so high up on my chair though I mightn't have been there at all, in a way, for I sensed the proceedings might carry themselves from beginning to end far removed from my presence.

"I am told that the wage of a Roundot mineworker is five dollars a day," Barnes said. "Five dollars a day, less the cost of his tools, to brave the darkness and the depths."

Amos Edwards, front and centre, who co-owned the mine with his brother Elijah, shifted a little in his seat and slowly crossed his legs.

"Fanny, behind me, garners double. Double and then some," said Barnes. "Six sittings a day, one hour for a sitting, two dollars an hour—that's a twelve-dollar take. Fanny, a girl of seventeen, making two times as much as the grown men of Roundot, and then in the comfort of her parlour, where the air is as crisp and as clear as a bell. As crisp and as clear as a bell," he repeated, "unless you count the Spirits in it."

Laughter took the small committee, none so loud as Amos Edwards. Shadrach Barnes paced back and forth, careful not to turn around.

"Roundot might've called many men to its aid. I, of course, am only one. And being that man which Roundot chose, to wit, a disciple of science and reason, I have studied long and hard for three days past inside this room to determine for all, to the best of my knowing, whether Fanny Conant can communicate with spirits. My inquiries have focused on the rap, by and large, the so-called grammar of the spirits. The inhuman sound that they use to express the sort of words I'm saying now. Yet far too human, I should say. As I have tried, gamely, to prove. And yet which due to some vile cunning, some legerdemain unknown to me, Fanny Conant has concealed and still conceals how it is made. But what can we really expect from a girl who claims to commune with the dead?" said Barnes. "It is a question I ask, gentlemen, not of you, but rather instead of Fanny Conant, who has only to look inside herself to see the evil of her ways."

"Here, here," said Amos Edwards, rising slightly from his chair.

"Tell us what evils afflict her, Professor."

"I myself have developed a number of theories on how Miss Conant works the trick. Medically speaking," Barnes said and gave pause to finger the mandible prongs of his scope, "the rappings themselves may be ascribed to one of several dislocations. The ankles, the toes, the hips, the fingers, and most favourable to this end, sirs, the knees. Why the knees? Since wide, the knees. The knees are the broadest and thus the most pliable, specifically the tibia and femur," he said. "The former grates upon the latter when the muscles either side of the former are exerted, producing a percussive sound, and ample force to jar a table. Fanny Conant effects—or affects, I should say—a quite ingenious jamboree. Fanny is for the bandstand, sirs, to herald with flautists the coming of spring!"

The laughter came bolder this time, more relaxed. The gentlemen were settling in. I felt my eyes begin to dart, searching out the room's egresses.

Where were my parents? They had profited from me. And then they too had been too scared. Their daughter, held below the town and brought every night to the church of the elders. Or maybe they waited, distraught but resigned, in front of the great double doors in the dark. If I were to stand on the tips of my toes to see through the window surmounting the lintel, might I have seen them on their toes attempting as hard as they could to be near me?

Shadrach Barnes was down below. He was binding my feet with a sort of thick bandage. He did not speak as he did this, and I could see only the crown of his head. He wrapped and clipped and tied the bandage without ever once looking up at my face.

"Of course, when they do it in China," he said, "the women inflict it on themselves. The effect of the binding is purely cosmetic. They like to go on slender feet."

"Be sure she's not too nimble, sir," said the Minister Willets, his eyes resting on me. "She isn't far from getting up and bolting through that door."

"She is just about right, I think," said Barnes, and tightened the knot that he'd made in the bandage.

There was a fiddling at the door, and then it burst open, admitting the nighttime.

Someone laughed invisibly.

An object trailing smoke rolled in.

And as it rolled, the door slammed shut, and the room was suspended a moment in silence. One of the aldermen gathered himself and he walked down the aisle to survey what it was. His footsteps sounded very loud. The object was still trailing smoke when he reached it and then it exploded in his face. It was fondly what the boys would call a sparkling torpedo.

The alderman yelled and shot upright. He clutched his eyes and limped away. A couple of local Roundot boys separated from the darkness beyond the open door.

They carried torpedoes of all shapes and sizes, ones to lob and ones to hold, and they lit them at once, as in some ceremony, and came on holding flames like monks.

The women, who'd been standing in the back of the room, who I'd hardly been aware were there, cried and came forward, a tide of them, running, to tamp the things before they went. The mine-owner, Edwards, looked shrewdly content. He leaned and whispered something in the county judge's ear.

Shadrach Barnes stood patiently, his hand upon his chin.

The pack of torpedoes went up, a sortie. The women, too late, fled clutching their bonnets. The room was filled with brilliant shapes and oppressively violent cracks and bangs. I stared for a moment, unable to move. And then I remembered my feet, lashed together.

Sweat was spreading through my clothes and trickling down my bandaged legs.

Shadrach Barnes was still, like me. He was standing at the head of the long line of tables and watching the proceedings down the middle of the aisle. He stood with his arms crossed, his necktie bunched up, strange, wild lights playing over his face.

"Now wasn't that a proper shock?" said one of the wives, who had mounted the table and was holding protectively onto my arm. "I trust you're holding up all right through all of these hooligan antics, Miss Conant."

Please don't make me go downstairs, I tried to convey with my eyes, without speaking, but the woman would not look at me, as if she'd been instructed.

I tried to pull my right arm free, but the woman who held it was uniquely strong so I hauled myself off of my chair into space, not caring what happened, just wanting my freedom, and I went swinging out in a sort of drunk circle anchored by the strong one's arm. A second woman joined the first upon the stage and wrenched me back, assisted by a stouter third. I kicked with my legs but they targeted no one, just lifted me slightly off the ground.

"This isn't right," I think I yelled. My voice was unthinkably loud in the silence. "This isn't right. This isn't right."

"Do not be alarmed," said Shadrach Barnes. "Miss Conant is afflicted with the bilious derangement. It is yet another symptom of the mediomania that compels her to sit there and lie to our faces. Spiritualism, womanism, bloomerism, abolition—all variants of the selfsame affliction. And now, gentlemen, they have driven her mad."

Everyone nodded thoughtfully as I was dragged across the room.

"Go easy now, miss," said one of the women. "You'll only make it harder on yourself if you fight."

"Motion to reconvene," said Barnes, "when I have dredged this mystery further. Thanks to you boys for the most rousing show. And to the rest of you, goodnight."