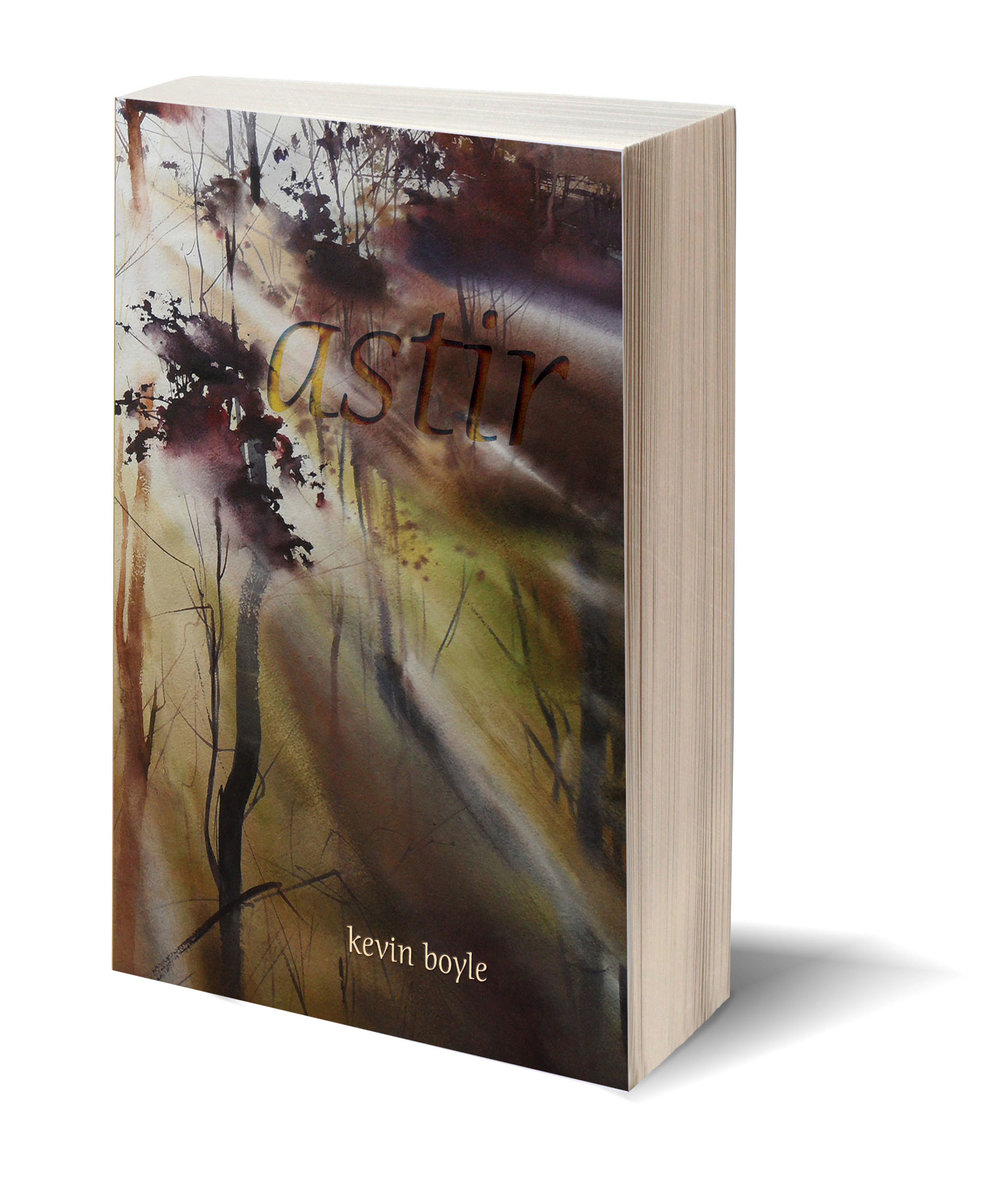

Astir

By Kevin Boyle

Jacar Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Liz Purvis

Kevin Boyle's latest collection of poetry revolves around themes of family, restlessness, the inevitability of death, and the pressing, sacrosanct desire to communicate. In his work, a man wants to tell his daughter, "Everything will be like this . . . Everything lost / will be inside you in some way" ("They Do Her Bidding"). Another tries to explain a play called "the suicide squeeze" to an apprehensive softball team. In yet another, an imagined Leda in "Leda and Swans," writes letters "to her absent lover, her distant god," attempting to share her life and children with a being who does not answer.

The desire to communicate and, at times, the failure to do so, surfaces frequently throughout Astir. When there is failure, a sense of anxiety ensues. In "Unruh," one of the anchoring poems of the collection, the speaker recalls his days of delivering newspapers as a boy, and we see that his fundamental traits have not changed; now, as then, he is "restless, uneasy, anxious, unsettled," and the list goes on. Indeed, the speaker puzzles over the word, "Unruh," the name of the street he worked on, how it means restlessness in German, and how fitting it is that he paced it daily. Here, as in many of the poems in this collection, the speaker is often unsettled, not because of his aloneness, but because of what he discovers of himself and the world while he is in it.

In "Clairvoyant," a boy again finds himself unsettled by the world, this time on an ice-skating excursion with his family. The picture Boyle paints here is a peaceful one—brothers and sisters skating happily, a mother guarding their fragile thermoses on the bank—but the speaker recalls how he and his father are unable to participate in the revelry, "standing on ice in [their] galoshes," relegating themselves to the sidelines as the rest of the family enjoys this moment. While the boy's father claims "immigrants couldn't skate," the boy's apprehension seems caused not by physical inability, but instead a kind of fear paralysis. He's an empathetic character, this speaker who says he finds himself more at ease:

in the oxygen tent where I'd vacation alone in the hospital,

all lungs and claustrophobic murmuring, than on ice

where, not far below us, a river was moving, tumbling

He's afraid more of imagined possibilities than the real dangers he faces, of which the reader only sees this small hint. This move is interesting, and it seems to indicate that, for this speaker, the imagined dangers are more fully formed, more daunting than any quantifiable fear of imminent danger. Describing his hospital stay in an oxygen tent as "vacation" already makes that event seem calmer, more peaceful, than this moment on the ice in which he imagines everything that might go wrong.

Older now, the speaker seems to recognize the childishness of his fears then ("how fearful I was," he writes) though, in the poem, his childish anxieties are understandable, relatable, real: his siblings skate across the ice and he worries they will run away to another state or fall through the ice; or that dead soldiers float under the frozen sheet, just below their skating feet; or that his parents will move to another continent, vanishing from their lives. The speaker also notes that he prays, as if in an effort to assuage his fears, but still worries. There's a religious undercurrent here, even in regards to his parents, for whom he fears that "their bodies wouldn't be temples of the Holy Spirit / but temples in ruin" and, while we're not given any specific reason for this concern within "Clairvoyant," other poems surrounding it portray a child whose religious upbringing may have set the foundation for his uneasy, restless temperament.

There's often a religiosity to the way many of Boyle's speakers navigate through their worlds, but there's also a rich sensuality in the biblical allusions. In "The Incarnation," a speaker reminisces about a former parish's unique form of singles meetings and how, over the course of the night, those involved "went from spiritmen / to pure bodies," how the façade of church broke down as the nights went on, though that too was in its own way holy:

[I]n that

sacred time after 2 AM we'd begin to unloosen

the stiffened nipples from their bras, or allow

our own zippers to be toyed with, just off Fifth

and Ashdale where the cops would ride right past . . .

as they watched us bring our bodies into communion.

The speaker here puzzles over his memories—surely this wasn't what The Church intended, but then again—he looks back, finds that in some ways these meetings could be called successful, that "nearly all have married in the faith we've lost." Even a speaker's sister in a later poem, "Vows," loses her faith; she once became a nun "before she took everything off—dogma, priests, fellowship," and the speaker, who found a nunnery an excellent place to worship women, became enamored with another nun, "evanescent, lost / beneath the wimple and forehead guard." He whispers "I'll save you" to her on the beach, the moment both sensual and holy as he notes the provocatively "thigh-long" rosary at her side, as he draws "the sign of the cross / on her torso" with his lips.

Boyle's collection is a group of poems aching to be listened to, to be read and savored and hunted through for such excellent nuggets as the scene in "Clairvoyant," the boy fearfully imagining the floating dead in a frozen river, "their feet / touching bottom without pushing back."

These poems work through emotions any reader can relate to: feelings of anxiety, questions of belonging, the inevitable restless worrying about fitting in, even in places the self knows it belongs. Boyle's poems puzzle through how to deal with that, dwelling in these moments of tension. After all, as he tells us in "Things I Knew I Loved and Didn't Know I Loved," a poem after Nazim Hikmet: "the journey and destination are both important, no?"