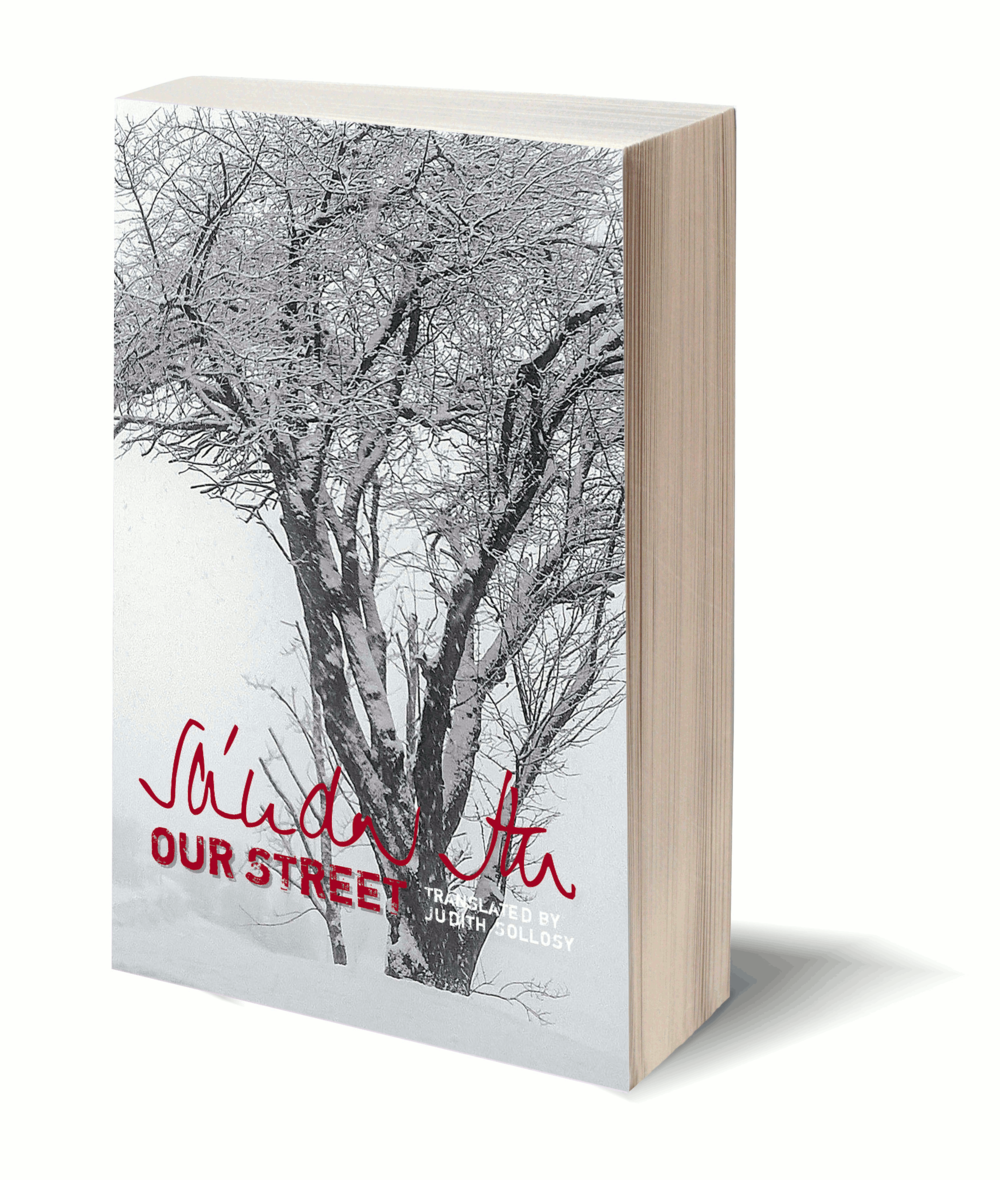

Our Street

By Sándor Tar

|

|

|---|

Uncle Vida

The street is waiting for the mailman. His cheeks are ruddy and he has a moustache; he wears a blue uniform and a green cape with a small red ribbon pinned to it. Around here unruly horses get ribbons like this tied to the harness, so people should be warned and not stroke them. The mailman does his rounds on a motorbike with a sidecar, and he doesn't have to be offered a drink anymore either, like before. Before, he did his rounds on a bicycle and people were expected to offer him a glass of pálinka or wine that he'd gulp down after a show of reluctance. And he'd take the tip, too, which came to twenty or thirty forints, a veritable fortune around here, with pensions being what they are. By noontime he couldn't sit on his bike, just push it along. Yes, ma'am, yes, sir, he'd holler when asked, tomorrow. You'll have it tomorrow! Fine, dearie, fine, but bring it in the morning before it gets as hot as it is now! If he staggered and fell he was dragged into a nearby house, rested a bit, then continued his rounds. In the afternoon he works as a hired hand, he plows the land with a horse, takes on shipments, prunes the vine. He's respected, because he's a hard worker, and nobody has ever stolen from him.

The street consists of thirty to forty houses on the village outskirts. At the upper end of the street there's a pub and a bus stop. Half the people are retired or live off of unemployment, how they manage nobody knows, least of all themselves. The houses are of varying sizes, some big, some small, each with a small garden. Some people even own a bit of land, but what's the use, Uncle Vida says, when regardless of what you grow, there are no takers. The state had the cows butchered, while those that kept theirs now have to milk them and feed them and spread the dung. As for the milk, nobody wants that either, and fattening a pig's not worth it, the fodder costs money, and then the slaughterhouse, they either take it or not, and for what? For peanuts. Besides, an animal's not like TV, you can't switch it off and go vacationing or to the movies or whatnot. The livestock's gotta be fed, Sundays and holidays included. Animals get hungry. Sunday. Every day. Several times a day. People don't think about that.

Uncle Vida is a well-read man, and sensible. He's just turned seventy. He owns five holds of land, a vineyard, a horse, a cart. He grows corn, sunflower, cabbage. He'd like to take his apples to market, too, but these days people won't eat anything but oranges and bananas, he says. He says that in the spring he buys cabbage seedlings for two or three forints a piece, and come fall, a head will fetch no more at the market than the seedling price, provided anybody wants it, of course, whereas it needs tending year around, hoeing and watering and sprinkling with insecticides, and even so it either turns out all right, or not. It's the same with everything, Uncle Vida says. I can't eat it all myself, he says, and what I don't grow, I have to buy. Like bread. And shoes. And there's the electric bill, the water, taxes. Everything. Everything costs money. But where am I to get it, Uncle Vida asks. I don't have a pension. I wouldn't mind selling things now and then, he says, but who'd buy them? People don't have money. I don't know what's to come of this, he says.

This is Crooked Street, he says. It winds around, and that's what we always called it, crooked, even when it went by other names. It's been called Ságvári,[1] and now Radnóti,[2] except nobody calls it that, not even the mailman or the chimney sweep. Nobody. When anybody comes asking for it by name, people take a good look at him, then ask who he'd be wanting. People around here don't know street numbers, Uncle Vida says, not even their own. The other day Aunt Kiss said to the doctor, doctor, dearie, what do I have to know the street number for? I can find my way home without it.

This is a hillside. It used to reach down to the stream, but there's nothing there now except a thicket. It's dried up. My father and the others used to go fishing there. Things were different back then, Uncle Vida says. As for the street, it took shape just like all the others. A cart drove along, then a second, and then a third, the tenth, the thousandth, each driving along the groove. There was plenty of mud for adobe. Today some houses have split levels. And there's even a concrete sidewalk, but only on the upper side. When it rains the water runs down to the side below, says Uncle Vida. For those that live there it's bad, he says, and there's lots of bickering, because the people living above dig grooves to divert the water and the hogs stand belly-deep in it and the rugs come floating out into the yard. But it's been some time since we've had that sort of rain, he says.

Our fathers and grandfathers could still manage to give a piece of land to each of their children, and a house, Uncle Vida says. We were expected to add to it, work hard so we could pass something on to our children, too. But that's not how it turned out. The co-op came[3] and the young people left empty handed to work in the mines or on construction sites, or at the foundry. Most of them never came back, Uncle Vida says. Then those that were born after them left, too. They went off to school, the factories, Debrecen, Pest. Wherever. And now they're trooping back, hungry and penniless. They drink and loaf about. They play cards. They live off the old folk and wait for the mailman. Some wait for their relief, others for their pension. Money. They're all waiting for money. Then when the money comes, it's payback time, oh yes, each man what he owes the other. Misi's pub, the shop, Sarkadi, Pintér. Three houses sell wine and pálinka, Uncle Vida says, on credit, otherwise they couldn't get rid of it. It's poor wine, it's bad wine. They make hedge wine from the rape and add it to the wine. By Easter it's pure mold. Then they skim the top off, add sulfur and sugar, and sell it by the glass or bottle. They ask a stiff price, but considering that people can't pay anyway, what's the harm? Strong, good looking young men stand around under this window looking out or idle about outside with nothing to do. Nobody wants to do the raking anymore, Uncle Vida says, or milk the cow, or feed the pigs. They won't sit atop a cart neither. They'd rather walk alongside or ride a bike. At home, they bicker with their wives or parents. They get divorced. There's all these handsome new houses, some with six rooms and split levels, burdened with mortgages, and the head of the household out of work, and there are children, too, they signed a contract to have them[4] and got promised the moon, and now there's nothing, just the shit hitting the fan. Then after a while the wife gets fed up and wants a divorce. That's how things stand today. And the houses, Uncle Vida says, they're up for sale. But whose gonna buy them, he says.

Uncle Vida's wife died four years ago, come Christmas. Every death and accident in the family happened on Christmas, Uncle Vida says, and he wouldn't mind if he never saw another Christmas as long as he lived. First it was his brother. He was shaving when all of a sudden he sat down and said, oh my god. But by then his head was blue, then it went black. He was gone just like that, sitting on a chair. His leg, too, got broke on Christmas. The pig pressed it against the fence and refused to budge.

Uncle Vida lives with his son, though everybody knows that it's his illness that brought him back. He used to work in Diósgyőr,[5] but after a time the fumes and the smoke ruined his lungs, but the real problem is that his wife walked out on him when he was taken ill, Uncle Vida says. His mind is sick, too, he says, it's his nerves, damn it, that's why he won't get well. They had a car and an apartment. Everything. And now he's just sitting there, Uncle Vida says, or lying in bed ill with nobody to talk to him, not so much as a handshake. He can't go out or visit people because he's got trouble with his lungs. He's not contagious, Uncle Vida says, they said so in the hospital, or they wouldn't have let him out. But even so. We took him everywhere you can think of, Uncle Vida says, before his wife left him. We paid through the nose. We gave money to them all in the hospital, even the elevator man. He can't sleep and he can't stay awake. At night he gags and coughs like the devil. I get up, go sit next to him, try to help him up. Then, half way in my lap, he dozes off like that, like a child. I took him to Doctor Szabó in the village, he's an old man, retired, to find out what's wrong. I'll give you ten thousand forints, I said, if you make him better, twenty if you tell me the truth. If you cure him, you can ask for the moon. Mr. Vida, the doctor said, don't waste your money. Your son won't ever recover. Give him whatever he wants. He hasn't got much time left. Just like that. In short, we all got our cross to bear. Mine is this. I can still work, even at my age, but this, this I can't handle, Uncle Vida says. I kept telling my wife, look, we need two or three more children, that's the real thing. But no. She may have been right, of course. For all we know, she said, we won't be able to bring even this one up properly. It was wartime and I was at the front. There was no guarantee I'd be back, Uncle Vida says. And now, this. There's no telling, ever, what the future holds.

I don't take anybody inside my house, not even into the yard, I don't want people saying it was me that made them sick, Uncle Vida says. I wash and cook and clean. My house is as neat as anybody's. Inside and out. But people won't shake hands with me neither anymore, Uncle Vida says. The Harap boy says to me the other day, don't take it to heart Uncle Vida, he says, but I got my child to consider. Fine, I say to him, you go do that, but you don't know who drank from your glass or bottle in the pub before you, do you? It could've been me. Or the Dorogi boy's horse, because that's his bit of fun.

Every day, I take my boy two liters of red wine from Mrs. Sarkadi, Uncle Vida says, because she sells good wine. To me, at any rate. What would you like to eat, I ask my boy. And drink. But he won't eat. Just the wine, the wine, that he forces down. And nothing else. I'd gladly bring him more wine, but he won't drink it. Sometimes he can't even keep the two liters down. He won't drink my wine either, just this. Doctor Szabó said, too, that red is better for him. We get on nice and quiet, who knows for how much longer. If there'd be somebody that could pass his illness on to me and my life on to him, I'd kiss his hand. But there's no such man.

When he got married, Uncle Vida built himself a house out of mud and wattle and beams. Back then, his house was the fifth on the street. Nice dry walls half a meter thick, the partitions thinner, warm in winter, cool in summer. There was an oven, too, but he dismantled it when the local shop started selling bread and it didn't have to be made at home anymore. There was nothing to make it from anyway. You can climb up to the attic from the porch, but there's nothing there. A shed with corn, a stable, pigpens, a small garden in front of the house. In summer gladiolas bloom there, and other things, too, perennials that Uncle Vida's wife had planted. They come up by themselves every year. Outside, by the fence, there's a small bench. It's nice to sit there and smoke and watch the world go by. Everything's just fine, considering.

[1] Endre Ságvári (1913–1944): A Jew, chief organizer of the left-wing youth movement and active opponent of the fascist Arrow Cross. He died in a gunfight on July 27, 1944,when the police tried to arrest him and he pulled a gun on them.

[2] Miklós Radnóti (1909–1944): Jewish poet, scholar, and literary translator, called up into forced labor in May 1944. Too sick and exhausted to continue his forced march through northern Hungary, he was shot, along with 21 others, in early November 1944 on orders of lieutenant-colonel Ede Marányi.

[3] The co-op: The cooperative movement became a major priority of the newly established Communist government in 1948. The object was the large-scale, socialist industrialization of Hungarian agriculture. Forced into producers' cooperatives, the peasants, left without land and livestock (they were allowed to keep only two pigs and one cow), began to troop into the towns in search of livelihood.

[4] They signed a contract: During the Kádár years (1956–1989) couples could obtain low interest loans for housing by signing a promissory contract to have at least two children.

[5] Diósgyőr: During the Kádár years Diósgyőr was a major center of heavy industry, a Communist showcase with a huge steel factory.