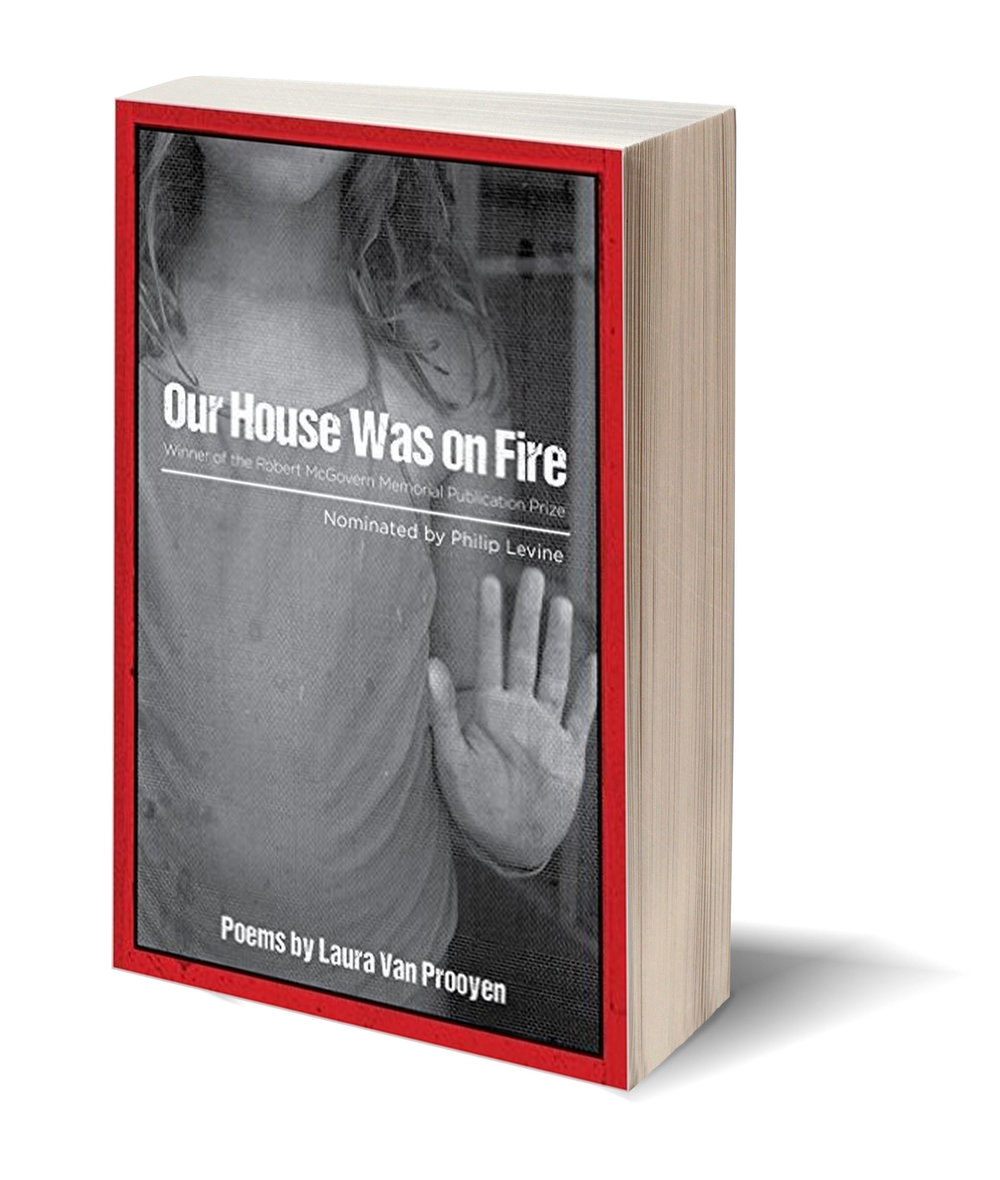

Our House Was on Fire

By Laura Van Prooyen

Ashland Poetry Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Allison Donohue

Nearly halfway through Laura Van Prooyen's Our House Was on Fire, the reader will encounter the following line in "At the Door": "Just make myself sick with happiness / or loneliness because who can tell the difference." Van Prooyen's honest collection vacillates between extremes – happiness and loneliness, the real and the imagined. "At the Door" begins with a tone of mysterious indulgence, a tone which trails a large portion of Van Prooyen's poems throughout her section-less collection. "Let there be," it begins, "an apartment / with nothing but a pillow, a window / where I see a fire escape or mountain or anything."

Van Prooyen's speaker indulges the "what if," the "could be," and the possibility that is no longer a possibility. All of this stems from the collection's heart: a daughter facing a terminal illness, and a mother facing her daughter's illness. Van Prooyen, rather than turning to the hospital room or the technicalities behind treating the disease, turns instead to the natural world. These poems deal largely with the way danger cases our daily lives; how the mother and daughter deal with this is through the lens of nature. "How Quickly Nothing Is Familiar" begins, "First, the headless vireo. / Then the labrador sprung from the brush. And now / the man with his hand between the scruff / and collar leading the dog away." Or, likewise, in "Eighth Stage of Love," the poem concludes with the following:

Do you see? I cannot be the only one who noticed

that hawk. Or how it perched in the oakbefore it ambushed something by our garage. Tell me

you want to know what's wrong.

While nature may be thought of as wondrous and beautiful, Van Prooyen's poems pull back the beauty-blinding curtain and depict primal nature – with pins, nettles, birds who hunt, and who sing not always happily. With loneliness and unhappiness comes the question "What if?" Van Prooyen delves deeply into this question in the collection's introductory poem, "Migration," in which the speaker wakes in a dream with another man beside her, a man who "was not the one next to her sleeping." And in only the third line of the poem, doubt rises with the single word "if." The speaker is already unsure. There is grayness here, a fog upon the truth or outcome, upon the way in which one is able to digest such sadness and truth. Van Prooyen's poems oscillate between what is and what could have been; "Migration" wings the collection into a sort of flight between one and the other.

What the collection spends a large amount of time turning from – the illness of the child – it spends the remaining amount of the time looking at head on. In "Hummingbird," the daughter's death is wholly apparent; as she and her mother lay in bed, the mother confesses, "whose ribs I feel when I hold her close / to keep her for as many hours / as I can before her heart / defies us both." Where the collection morphs is when these raw poems about the child's inevitable death are placed beside poems in which the speaker – the mother, presumably – entertains a life she might have had without her daughter. "Perennial" opens:

It can be like this. One day

to wake up thinking goldenrod. Coneflower.

Not as suggestions, but directives,

so that I load the children into the car

and go. And it can be . . .

Hesitantly, the speaker imagines through the present tense, almost for a moment believing, that this alternate possibility exists:

It is then I wonder

what would have happened

if I rose from bed thinking: tiger

or lily. Or if

I had stayed

that one night long ago.

And can we blame the speaker for this? For wanting an imaginative exit from the troubling truth of having given life to a young child who will not be able to live it? We cannot. There is a moment of certainty at the collection's conclusion in which the speaker confronts her faithlessness, if it can be called that. I prefer, however, to call it humanness. In "Our Story in the Snow" the speaker wakes early. Leaving the "you" in bed, she goes outside to shovel the driveway. While shoveling, she confesses, "I'm sorry there was a time / I contemplated our bookshelf and wondered / who would keep it when we split." Van Prooyen does not shy away from honest statement. Coupled with imagery, the statements speak loudly. For example, the way in which "Our Story in the Snow" finishes: "I'm different now, / but probably / I'm not. Except I'm here in my mis-matched / long johns with unbrushed teeth." And the speaker finishes in the freezing weather, shoveling what snow fell while the two of them had been asleep.

A brave collection, a collection that should not leave the bedside for many months, Our House Was on Fire documents a past, a present, and a future in which the speaker copes with pending or suffered loss. Where nature appears razed, it also appears full and growing outwards in nearly every poem. Laura Van Prooyen has looked something difficult in the eye and has continued to look. After all, ". . . the world can be broken, / but beautiful."