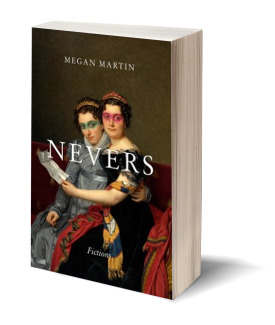

Nevers

By Megan Martin

Caketrain Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Nick Kocz

Years ago, at a writers' conference, I uttered a witticism. A bunch of us were talking shop after hours around a picnic table and, after bitching and moaning about our day jobs, we got onto the subject of the professional lives we give to the characters we write. "Do you know what the number one job for most fictional characters is?" I asked. A few people made guesses: student? housewife? detective? I shook my head. "Nope. The most popular job for a fictional character is deadbeat alcoholic loser."

My new friends laughed, but then, around the picnic table, people put down their beer bottles and their wine glasses.

"Why do you think that is?" someone asked.

Until the question was asked, I had never given it serious thought; however, the answer came to me with sizzling clarity: "It's because that's what we all personally fear will become of us; we're all afraid we're nothing but a bunch of deadbeat alcoholic losers."

The first-person persona crafted by Megan Martin as the narrator in Nevers, a linked flash fiction collection, is just such a deadbeat alcoholic loser. Because Martin's protagonist also happens to be a struggling writer, Nevers focuses on how the two conditions are related.

Martin's protagonist writes poems, stories, and more: "I have become a person who has for ten years been writing a novel in a unicorn notebook that nobody will ever see." She attends informal writing groups, public readings, and drunken parties, and clings hard to ideas about the nature of art. She runs through a series of boyfriends, muses, well-meaning friends and family members, and gazes longingly past the back patios of her subdivision at a pair of wild foxes ("The first is satisfied with her mediocrity, but I can't tell whether she is about to murder, seduce, or abandon the second.") that periodically turn up in this collection.

However, what sticks with this reader most are the protagonist's anxieties. Like most writers at the start of their careers, she struggles—financially, professionally, and emotionally. "I still wear caution tape around my heart," she admits. Money is tight, and alcohol ("I cart mini booze bottles around in my pocket and call them my 'liquor cabinet.'") can only go so far in soothing her anguish. Martin's protagonist is attuned to the real and, in some cases, imagined derision that greets her writing. As her neighbor tells her at one point, "Participating in the world of literature just makes you economically unstable, homeless-looking, and mentally ill—and in no way special."

Disdaining standard literary convention in favor of a more aggressively experimental aesthetic, she tries to "invent new ways to avoid plots and characters." As she concedes, "My strong beliefs about what is absolutely fucking not a piece of art prevent me from making anything a person might actually want to read." Her mother has other ideas about how she should pursue her craft. Use "a compass to make plotlines that are as perfect as circles!" the mother suggests. "[S]olve all [your] character's problems like an equation." When the narrator rejects her mother's advice, her mother makes her feel like she is destined for "an empty and childless and husbandless life of putting words on paper." After giving a particularly dispiriting reading, she thinks, "I am so dumb for not joining the Peace Corps or becoming a nun or a kindergarten teacher or a mommy."

She's engulfed by a particular writerly brand of self-loathing. "I am sick and tired of developing characters," she tells us. "I am the cheapest prostitute ever, forever peddling rouge, diseased syllables in the alleyways, lifting my legs to piss a fourteen-page fire." While her peers' poems succeed "like the Sistine Chapel's ceiling," her own work "spin[s] a yawn that goes whoop-de-do in a lax breeze. It is what I like. It is a flaccid little pinwheel of failure."

As the book progresses, the vitriol of her self-excoriations increases. At one point, Martin's narrator lashes out at the real-life Megan Martin. "A poet is not a seer—do you romanticize yourself so fancily, Megan fucking Martin? You're as destitute as the rest of us! You have a rancid groin area! Don't ask for her autograph! She doesn't wash after masturbating!"

It gets worse.

In "And Another Muse Fails," one of the collection's more surreal pieces, a writer-husband appears on the scene, one of those "old white guy poets" who seem specifically placed on this planet to destroy the confidence of female writers. "He rapes me in the alley," the narrator tells us, "(I was asking for it, writing so dumb, not following instructions, just like a woman, blah blah blah), then drops me off at the Home for Orphaned Muses where I'll henceforth be ignored entirely by all writers, the general public, the academy, etc."

The Writing Life. What exactly is meant by that phrase? I see it every so often ("Immerse Yourself in the Writing Life!") in advertisements trying to entice me to enroll in a summer writing conference, writers' colony, or MFA program. Typically, the ads will feature a photo of a woman journaling while sitting on a majestic hill overlooking running water. Or, occasionally, the picture will be of a man alone in a verdant forest with his laptop.

I hate those ads.

They imply that "the writing life" is somehow idyllic, a life that takes place in a separate reality from that which governs most other kinds of lives and vocations. Offhand, I can't think of a single writer who works primarily when seated on a forest stump or at a perch on a breathtakingly spectacular hillside vista.

On the advice of a guy I met in my MFA program [full disclosure: I've succumbed to duplicitous advertising], I'm reading Stephen King's On Writing. It's actually pretty good. King, who came of age in the 1960s, disparages his generation ("We had a chance to change the world and opted for the Home Shopping Network instead"). When he was in college, "there was a view among the student writers I knew at the time that good writing came spontaneously, in an uprush of feeling that had to be caught at once […]. Would-be poets were living in a dewy Tolkein-tinged world, catching poems out of the ether. It was pretty much unanimous: serious art came from… out there."

Say what you will about King's prose, but judging by his published output, you must concede his work-rate is prodigious. Words, pages, and manuscripts don't just materialize from sudden jolts of inspiration but accrue through everyday hard work. In King's early years, he probably bitched and moaned about his day jobs doing laundry, dying textiles, and teaching, yet he wrote during lunch breaks, nights, and weekends.

I sense the same kind of work ethic from Martin's unnamed protagonist. She and an idealized boyfriend work "'rewarding' low-wage jobs that will allow us ample time to make our shitty garbage art." She is not a dilettante; she does not sit around waiting for good fortune to strike; as depressing and frustrating as it is, she carves out the time to write.

Though you won't see her picture in the ads that appear in Poets & Writers, she is living The Writing Life.

But are the trials and tribulations, the uncertainty and anxieties inherent in The Writing Life, worth it? Martin's narrator believes that they are: "'I will keep on believing so goddamned ferociously in art,' I say, especially on days when I cannot think of a single reason why anyone would wish this on herself."

Moments of insight appear frequently throughout Nevers. While waiting for a phone call at the conclusion of "A Pink Anything Can Revive," the narrator wonders if "there could be a magical something out there waiting to lift" her from her doldrums.

I remembered that time as a kid, that rabbit's foot in the gumball machine, dyed yellow and black, those little leathery pads of skin, so fresh it was still leaking blood. I wanted it—oh, I fucking wanted it. Right then something was happening that was meant just for me!

Instead the phone rang. I explained the memory I had not thought of in so long excitedly into the receiver.

"When it came out it bloodied my hands," I said. "It was so soft, so warm."

In "Fuck You Too, Person That I Loved," Martin's protagonist writes a scene in which a glass "gondola got smashed by an iceberg." The glass gondola is clearly metaphorical, "a symbol for life and art." At the story's conclusion, she asks, "Why would I try to set sail in a boat of glass?" The answer: "Because I could not understand why I could not."