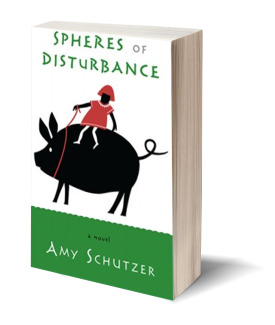

Spheres of Disturbance

By Amy Schutzer

Red Hen Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Jackie Thomas-Kennedy

Amy Schutzer's second novel, Spheres of Disturbance, brims with ambitious characters and the things they love to create: hand-carved bowls and macramé plant holders, gallery installations, and books of poetry. It is 1985 in an upstate New York town full of artists and would-be artists, a place where a garage sale includes a live musical performance, a place of such frenetic invention that casual conversation soon turns to lengthy expounding on the definition of art. Amidst the clutter of these amusingly self-important discussions are items of much deeper consequence: Sammy, a young woman, is watching her mother, Helen, die.

Sammy, one of Schutzer's stronger characters, is also one of the least consumed by her own creative pursuits. She is devoted to her mother, who has reconciled herself to numerous misfortunes: to the family that abandoned her, over thirty years ago, during her out-of-wedlock pregnancy; and to the fact that her death is approaching, and she wants to choose how her life ends. Helen seeks comfort in both Sammy and Sammy's girlfriend, Avery, an earnest poet who fears that her "thoughts are mired in clichés." Sammy and Avery provide Helen with whatever they can: lunches of "fresh haddock, brown rice, buckwheat, tofu," board games, and poetry readings. Avery faces the nearness of Helen's death in a way that Sammy cannot, and this is a frequent source of tension between them. Schutzer writes that Sammy "will not admit to the trajectory" of cancer, but Sammy is engrossed in her mother's palliative care—an admission, certainly, even if an unspoken one.

Sammy is her mother's only child. That she prefers not to speak of Helen's imminent death seems reasonable. She is described as "denying her mom's predicament. If she doesn't bring the cancer, or the prognosis, into focus, than the uncertainty remains just a predicament, and not a finality." This reads less as denial and more as a way to cope. When, immediately after sex, Avery demands, "when are you going to talk to me about Helen?" it's not clear why this is such an urgent matter in the first place. "I intend to be childish and not budge till you talk to me about Helen," Avery claims. What, we wonder, is she waiting for Sammy to say?

Avery is Helen's primary confidante, though Helen is also close to Sammy's employer, Joe, who she enlists to help her with a plan for the end of her life. She wants "to go in the river and float on down, eventually over Niagara Falls." Her timing coincides with the appearance of her estranged sisters, Rosie and Maureen; with Avery's massive garage sale; and with the birth of a litter of piglets at Avery's house. Schutzer delivers each of these scenes, and the general sense of growing chaos, with piercing descriptive skill. As the music stops at the garage sale, where everyone has converged, "[t]he rafters seem full of chords and harmonies, the notes settle onto the high wood." This lovely image prepares us for cacophonous resolution.

Beautiful imagery aside, Schutzer can be too generous with her characters. She crowds a community into these pages, and gives plentiful time to some of its weaker members. There are several chapters from the point of view of Charlotta, a pregnant pot-bellied pig, which are nicely written but do little to move the story along. Joe's wife, daughter, and sister—Marjorie, Darla, and Frances—each have struggles with their identities that might best be captured in another book. Avery's ex-girlfriend, Durga, is allegedly a formidable presence ("Durga was most definitely quicksand, and Avery had fallen in.") but she is laughably affected every time we see her, posturing like an insecure adolescent. Helen's sisters play a far more integral role to the story than the crowd in the garage.

Though one of the sisters, Maureen, fades into the background clamor, Rosie is fully realized. Her relationship with Will Silverman, a condescending lawyer, invites more character development than any other pair, including Sammy and Avery, the novel's central romance. Sammy and Avery are inextricably bound to Helen, whose illness infects their relationship by making Sammy withdraw. "Over the last year Sammy has tried to revert to a stranger [. . . .] The doubts Avery has come down to one: will Sammy allow love?" Avery's ultimate declaration is one of passivity: "the only way I can go forward is to be who I am, and let you be who you are."

By contrast, Helen's impending death evokes Rosie's strength, and allows her to stand up to the quietly tyrannical Will. (Convinced that "there's money to be made in finding missing persons," Will decides to sharpen his skills by leading the search for Helen.) Meek Rosie is stunned by Will's attention—and by his sexual appetite—but it occurs to her that she is "just the latest convenience." Will is dismissive of her concerns, controlling about her behavior, and demanding of her body. Eyeing his "glorious mouth," she concludes, "His biggest accomplishment was in how entirely she had fooled herself."

The moment when Rosie decides she is "done with [Will]" is brilliantly understated and utterly perceptive. Watching him tip the "flirty" cashiers in a donut shop, she understands how well she knows him, and how pathetic he is: "The teenage girls at the donut counter put him in a jaunty mood [. . . .] [H]e is a rooster, and a rooster has to crow. Any hen will do [. . . .] What he failed to realize is how it amused her, his ridiculous need to be paid attention to."

Donut World, full of plastic chairs and fluorescent lights, is also the accidental reunion site for the three sisters. Helen and Joe, in the process of enacting Helen's "plan," happen to stop at the same place where Rosie and Maureen are taking a break. The encounter among the groups is suitably uncomfortable. Maureen is startlingly rude; Will asserts authority ("I'm the family's attorney"); Helen tells Maureen, "I don't have enough breath left to list the ways I despise you"; and Rosie walks out of the shop with Helen and Joe.

The novel maintains focus during its brief time at Donut World. At Avery's, the multitude of characters come rushing back in, diluting the plot with their far less pressing concerns: the price of garage sale clothing, the fumbling of teenage flirtations, the arrival of pot-bellied piglets, the sneaking of cigarettes. None of these things seem to matter much, especially not when Helen is struggling to breathe.

The core of this novel is Sammy and Helen's family, along with a few of the people they allow into their lives. Schutzer's writing is best when it tends to the less self-conscious characters. Durga may be "[a] feminist witch" and a "back-to-the-land pioneer," and Frances may claim "the edge" is her "comfort zone," but the most compelling moments are quiet ones, unattached to conceits. Rosie leaves Will in a donut shop; Helen wishes for "[o]ne more time through the snow" as she walks outside; and Sammy tells her dying mother "it's okay, Mom, it's okay," when she isn't at all sure if it's true.