Elliot Cole

Listen: "Hanuman's Leap"

Last summer I saw, in a documentary about central Asian folk music, a manaschi–a Kyrgyz bard devoted to performing his national epic, Manas. He was inwardly transfixed but also dramatic and expressive, his body moved in a softly fluid gestural dance, his lines falling now patiently, now urgently, both hot and cool, poised and passionate, and endless. Though I didn't understand the language, there was much to enjoy–a guttural intensity to the voice, dramatic shifts in register and tempo, end and inner rhyme play, an all-possessing groove. I was also moved by his depth and singularity of purpose. He was the humble vessel of a vital myth of his people. His years of study, practice and performance had changed him, physically and spiritually. He doesn't so much perform the story as surrender to it, for days at a time.

I reflected sadly that, as the likelihood of my learning Kyrgyz (or Serbian, Finnish, Tagalog, Korean or any of the other languages in which traditional epic performances have survived the 20th century) I will never hear a traditional epic performed that I can understand. And, though I think of myself as having made a deep life-long commitment to music, the relationships I have with my repertoire are thin, skim–literate–compared to his deeply internalized surrender.

I decided to write my own. I was reading rapturously the Ramayana (in the luminous prose translation of Ramesh Menon). I chose a scene from it to rewrite and sing, a kind of warm up, in hopes of finding the first threads of a personal epic style.

It's now a year later, and I am still in the clutches of this single scene, with a mountain of work behind me and still a thrillingly unknown gulf ahead.

I have been deeply nourished by the work because it integrates what my world of professionalized composition has torn apart. Centuries of specialization have divorced The Composer from so much of music. We, by and large, do not face audiences directly–we have professional performers for that. We don't write our own texts–much safer to find a famous Poet in the public domain. We rarely memorize anything. We routinely write things we cannot play, and with notation software and MIDI playback (or, more broadly, literacy), we need not even feel our lines and rhythms in our bodies as we write them.

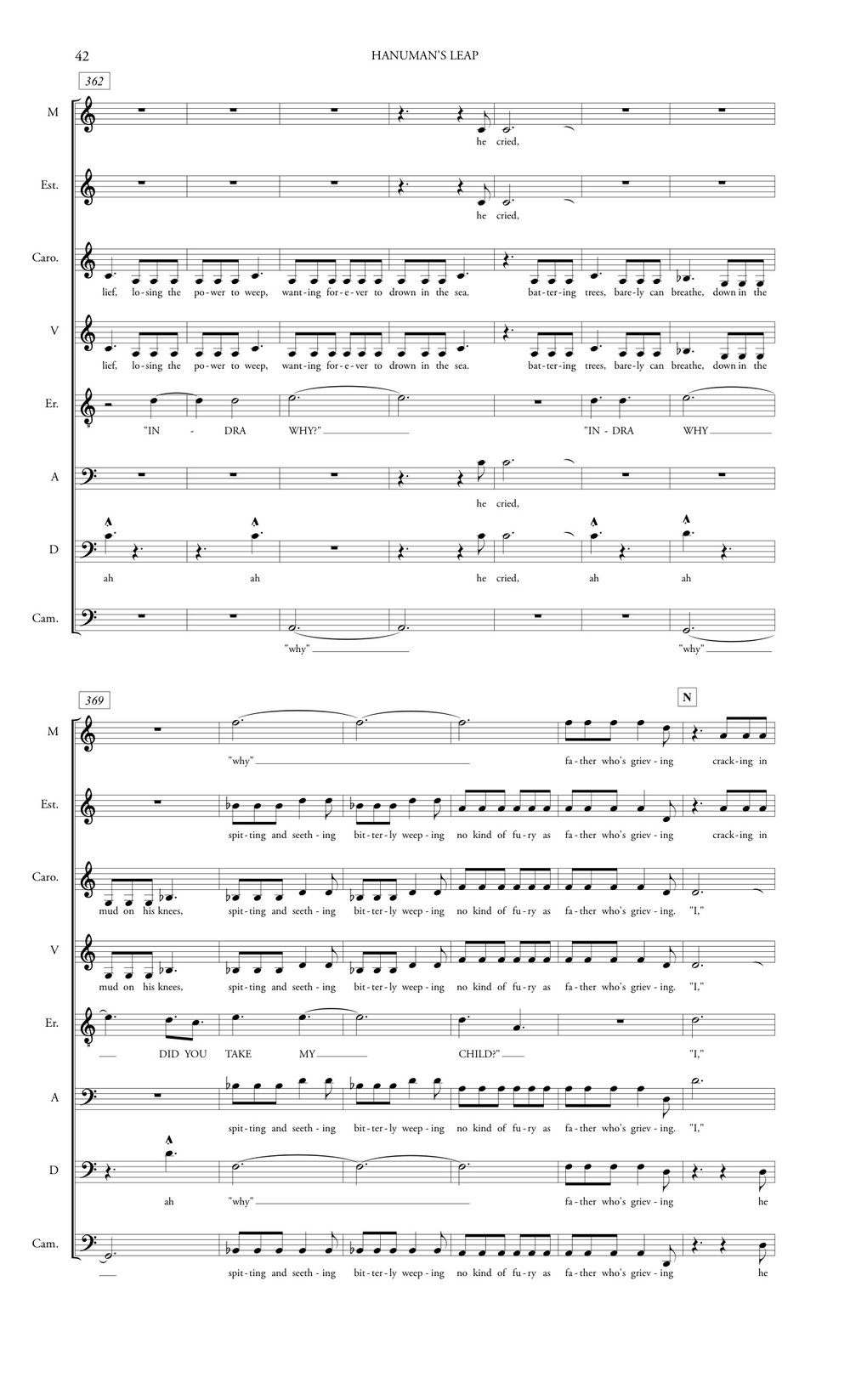

I reclaimed all of these roles in this work, and each vitalized the others. The rhythmic pulse propels the writing of the words; the content of the words suggests an affect and intonation; an affect and intonation suggests melodic line; a melodic line makes demands on rhythm; rhythmic logic is calculated bodily, intimations of dance, propelling new words. Grounding each of these translations immediately in the whole-body athletic of singing–constantly, hours on end–shaped it further: the placement of vowels, the possibility of diction, the flow of breath, the length of line, the micro-adjustments of rhythm demanded by articulation, are all differently possible in the various corners of my particular and imperfect voice. Polyphony (my greatest stylistic break from traditional performance) multiplies these considerations, and, by continually demanding solutions to polytextual and polymeric puzzles, connects language to that great musical source of generative energy, counterpoint.

Epic song was, after all, an Ur-art. Poetry was music, music was dance, all the sediment of a numinous wash of magic, trance, and prophecy. For me to do this work is not only to integrate my own personal amateurisms, a deep pleasure alone, but to explore their source, their original purpose and power. Our own enthusiasm for collaboration in the arts suggests, in part I think, a hunger for this kind of exploration. But after a year of this work, experiencing firsthand the co-creative vigor of these disciplines being practiced together, I now believe that the artist who integrates them in their own practice has access to something important that a collaborative team of specialized experts cannot.

This requires an embrace of amateurism. My own skills as writer, singer, composer, performer (and, recently, recording engineer and producer) are all-too-uneven. My betters surround me. I am open on all sides to critique–my primitivist romanticism, my catch-all exoticism, my essentialist naivete—

But aren't we all, in those few but exhilarating moments of creative contact, when the next step is not taken but revealed, when we are no longer pushing but are pulled, when we stop performing and surrender to our song, essentially naive?

Excerpt from Hanuman's Leap:

His jaw struck first,

the generous hand of earth a fist,

and all across the land could feel the blast:

it shook the forest by the roots,

it shook the stones of temples loose,

it rattled plates and glasses in the cupboards –

cattle spooked and stumbled in the pastures –

splitting cliffs and liberating boulders

and loosening the purses of misers,

tongues of thieves, and belts of lovers.

Vayu, god of the wind, father of Hanuman

blew across the ocean to the mountain.

He found the spot his favorite son had fallen on,

his father's heart was hoping, but was broken,

and his strength was gone.

He

cracking in grief

wanted to pull out his teeth

couldn't believe

He

needing relief

losing the power to weep

wanting forever to sleep

wanting to drown in the sea

He

battering trees

barely can breathe

down in the mud on his knees

spitting and seething

bitterly weeping

no kind of fury as

father who's grieving

"Indra!" he raged,

"Indra why?" he cried,

"Indra why did you take my child?"

"I," he raged.

"I will not," he cried.

"I will not breathe–"

"I will not breathe–my life–upon the earth–unless you raise him."

"This shall be my curse in boundless fury given:

I swear by Vishnu's thousand names in heaven

if my son dies, then the four-worlds with him."

And he shut himself inside a cave.