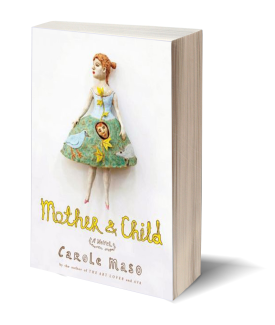

Mother and Child

By Carole Maso

Counterpoint |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Kathryn Houghton

One night, a maple tree splits in half and hundreds of bats fly out, starting Carole Maso's titular mother and child on a journey that calls into question the very ideas of life, death, and reality. It is a journey that takes the reader to the Twin Towers of New York City and the icy expanse of the North Pole and on which, when the child begs her mother to assure her of their existence, the mother replies only by saying, "Silly girl."

Carole Maso's Mother and Child is by turns haunting and magical as it explores the deep connection between a mother and her child. Neither is ever referred to by name, though other characters are, and the ambiguity of the pronouns only adds to this sense of closeness: when the she is unclear, Maso could be referring to either the mother or the child—or, perhaps, to both of them.

The mother and child live in the Valley, a place where men have all but vanished, gone off to fight a distant war. One day the Spiegelpalais appears—a presence that is never clarified or explained and that is only described once:

It had come with the Great Wind, under the cover of the night, while the Valley had been anesthetized, and now that morning had arrived, and the mist was beginning to lift, and the wind had at last departed…White sails could be discerned in the distance and a faint music—an accordion, cowbells, a most charming sound, and so inviting, as if conjured not played, could be heard wafting across the meadow.

Like the Spiegelpalais, there is much in the novel that is left unexplained, though no part of the story suffers for this. Instead, the reader explores the strangeness of the world right alongside the mother and child. When a cat kills a rabbit and the next day the rabbit reappears in the garden as a concrete statue, you aren't supposed to question but rather accept it right alongside the mother, who only scolds the cat for his actions: "now we have to live with this hare, standing erect, holding a basket, guarding his kind forever, in all seasons, in all weather, night and day." Later, when the mother and child begin to tell the Concrete Rabbit "their troubles, their thoughts, their ideas, their dreams," it makes sense, it fits.

Maso's refusal to distinguish between what is real and what might only be in her characters' minds reminds the reader that there are things more important than literal truth, that our desires, passions, and fears, while intangible, may best deserve the label of reality. The child, in whom the mother recognizes a certain "wisdom," knows this as well. She is afraid that "when the mother leaves the room, she is no longer anywhere at all. That she no longer exists on any level. She can't keep her mother together. And the child too has no color or form unless particles interact with the mother's consciousness."

The mother's own fears center around losing her daughter, either to time or to something more sinister. Her own death worries her as much as her child's because either would separate them. Throughout the novel, the Virgin Mary appears to the mother and child, calling them to her, and each time, the mother implores her, and God, for more time. She is so afraid of this change that at times the past, present, and future fuse together:

So coltish, that day on the lawn. The image indelible, but also vulnerable and porous, permeable, open to bruising or injury. And a medium girl here now, and at the same time a baby in her carriage under the same tree and a toddler toddling on the green grass and a teenager, suddenly sullen, and a grown woman now walking toward her mother who has not aged.

You don't have to be a parent to recognize the truth and tenderness in Maso's handling of parenthood. Her decision to use both the mother and the child makes this book inherently accessible. Helping the reader along, too, is Maso's signature lyrical style, which makes this book a true joy to read. The cadence of her sentences alone is enough to merit multiple reads of the book, but then the ending does its own part to make this a book worth exploring again and again as it asks the reader to let go and consider What if?