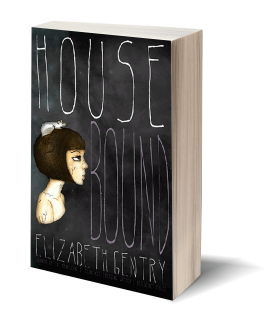

Housebound

By Elizabeth Gentry&Now Books |

|

|---|

On the other side of the creek, the path twisted through a series of blackberry bushes in bloom, then climbed a short rise that appeared to give way to a grassy knoll. Just before stepping into the open, Maggie envisioned a two-story house with peeling white paint. Upon entering the clearing a moment later, she felt unsurprised to discover a two-story house with peeling white paint. Overgrown holly bushes loomed on each side of the front porch. The house was like something she had read about in a book, both threatening and inviting, strange and familiar. She glanced in the direction of her own house, which the cane brake now hid, then took a step into the yard filled with shoulder-high weeds. In the middle of the lawn sat a rusty push mower, which someone had used to create a passage from the front porch to the gravel driveway at the right of the house, where an old gray sedan hunched in the grass. The road beyond the house quickly disappeared into the tree line.

Maggie was on the verge of turning around when the front door opened and a bald, bulky man stepped onto the porch to scrutinize her. She hesitated, remembering her sisters' reference to a prowling man and a fat lady. Before she spoke, however, a woman's voice called from deep within, as if the house itself was asking from its rocky foundation, "Who's there?" The man did not reply, but simply waited in the doorway. From politeness Maggie felt compelled to take a step or two forward, as if to answer for herself. The smell of sugar and chocolate wafted from inside. Then the question came again, closer now.

"I don't know," the man in the doorway finally called back gruffly. "But she's like a long-legged colt."

Maggie felt the inappropriateness of his remark and turned to go without a word. At the edge of the yard, she heard the woman's voice from behind her.

"Margaret? Is that you?"

Maggie turned to see a very wide woman with a thick black bun and large round glasses emerge from the shadows. She was holding a white plastic tube tipped with metal and appeared slightly distracted.

"You should come inside," she said, wiping one hand on a full red apron with white ruffles, "but just for a little while. The tramps roam the woods at night."

Maggie thought only Quinn believed in the transients who camped in the woods close to the train. When the man stepped back from the doorway, she hesitated one moment more before following the woman into the house. They entered a room to the right, which was laid with an ill-fitting carpet so thick and wrinkled that she wobbled when she walked across it. Against one wall, a sagging couch was covered with recipe books and whisks and metal mixing bowls. In the second room, white cake boxes cluttered a wooden table.

"You know me?" Maggie said as they slowly circled through the otherwise empty rooms toward the back of the house, passing a small bare kitchen.

"Well, of course," the fat lady replied without looking back. "You've changed well enough, though, after ten years or more. Taller and skinnier."

"Like a long-legged colt," the man's voice echoed above them. The two women had arrived at the base of a set of stairs leading to the second floor. At the top of the stairs the man's bare heel was just disappearing behind a doorway.

"Shut up, you old pervert!" the fat woman yelled. Maggie looked at the other rooms beyond the woman and realized that the first floor of the house was built in a circle with the stairway in the center. The man had taken the other direction and come out in front. "You'll like the attic well enough when you're stuck there," the woman grumbled. She handed Maggie the tube of frosting, then reached down to the base of the stairs to grasp a loop of coiled rope. With a huge groan, she seized the strap and lifted the staircase, which came up as a unit. When she had it raised above her head, she fitted the loop over a hook and took a long wooden staff that was leaning against the wall and propped it under the first stair.

Beneath them a new set of stairs lead down into the basement, where the scent of sugar hung heavy in the air. At the bottom, they arrived in a subterranean kitchen lit brightly with fluorescent bulbs, as if it were a laboratory, though for a moment Maggie had a vision of the room that this one had replaced, a dark workshop illuminated by a parrot lamp and littered with colored glass like a pirate's cave. Now, however, the walls were white and lined with white cabinets, a double sink, and a large oven. Concrete stairs ascending to the yard were visible through the window of a closed door. At the center of the room, a high wooden table served as an island, where a chocolate cake with red flowers awaited the further attentions of its maker.

"You can sit there," the fat lady said, pointing to a tall counter stool. Remembering her sisters' warnings, Maggie noted that the stool was too high for the woman to be able to sit on her, though her knees were still very prominent, feet tucked beneath her on the top bar of the stool. She had discovered today just how playful her sisters could be, however, which might also mean that they were simply liars. Besides, the fat lady might only laugh on your knee if you were very young, assuming that she was amusing you.

Since Maggie was clearly known to her hostess, she was afraid to insult her by asking for her name, which the fat lady did not think to give on her own. Instead, the woman simply went to the refrigerator and pulled out a cupcake with white frosting and sliced strawberries on top, handing it to Maggie. "Strawberry," she said. "A favorite of yours, if I recall."

"Thank you," Maggie said. She hesitated a moment, remembering her household's prohibition against sugar, then began to peel back the wrapper. "You know my sisters, too?" she said, as the woman returned to her icing.

"Of course. Though it's been a number of months since their last visit. It's the same with all of you, from your family. The reading family, swallowed by your stories. Your older brothers I also no longer see."

Maggie was perplexed. For years now, the only neighbors she visited with were the ones who lived along the road toward town and who exchanged polite words with the family on their weekly trip to the library. "And the little ones?" she asked. "Do they come?"

"Edwin comes sometimes. Not the ten-year-old he tells me about. Nor the smallest."

"Oh," Maggie hesitated. "My father?"

"Never your father, or not for a very long while anyway." The woman paused, pushing her glasses back onto the bridge of her nose. "We've got a thing about fathers around here. We don't much like them."

"You mean you and the man who answered the door?"

"Me and my own daughter, who, like you, is grown, but comes to visit. The man upstairs is a necessity. He replaced my husband. My husband, in any case, was paralyzed on one side. He walked with a cane. And so he wasn't as much good to me as I thought he might be and in many ways was very bad. But the paint must be scraped and the cakes delivered. And the man upstairs is no father in any case, of mine or anyone else's children."

Maggie wondered how long the man upstairs had been there, given that she had not seen any evidence of scraped paint. Still, she had no particular reason to be bothered by the woman's views on fathers, having only really noticed her own father today, the one day she had seen him do something besides read the newspaper or roam the property repairing fences. What she saw was that he was something of a heartless man, leaving her in the coffee shop all morning with the surging demands of the caffeine, but that he also might prove to be an insignificant one, now that she would not be living with him, abiding by his rules.

"I've been to the city today," Maggie said, "but on the whole we've been rather housebound for quite some time." She hoped in this way to offer some explanation for her long absence, in case she had hurt the woman's feelings. As she spoke, she wondered if being housebound were an entirely natural phenomenon, since the fat lady seemed to believe her family's behavior was unusual. There had been that big spring snow one year—how many years ago now? A decade perhaps—that kept them in far longer than their usual snows. Even their father had remained home from work, making the weather seem a kind of holiday at first, though their mother still taught them lessons between nursing the newest baby. But then the snow had remained for days, and they had all grown bored with it—with the tunnel that Warren dug in the garden and with the books that they could not exchange at the library and with watching the road for the brightly colored scarves of the kids from town who at that time still came to play.

They had grown quiet under the weight of the snow. They had grown uncomfortable with the presence of their father, who was not usually around so much and who expected things of them that were not clearly defined, having to do with how organized, efficient, or active they were. He became restless, with much in the way of excess movement from him, clomping to the barn in his boots, to the basement in his boots, up the stairs in his boots, as he covered windows with plastic and stuffed towels into holes and put to rights an already ordered supply of canned goods in the basement and pantry, then disappeared for long spells to shovel and check the fences. Upon her husband's return from these excursions, their mother looked up briefly and intently, as if she blamed the storm on him and wondered what they had all done to merit this kind of punishment. Perhaps then the weather had been the problem, the familiarity cultivated within the enclosed space growing into a silence that did not thaw when the eaves began dripping a few days later. Though the weather changed, nothing changed inside the house. Their father went back to work. They used less wood.

The woman executed a particularly intricate rose, then said, "If you went to the city, you must be preparing to leave."

"Yes," Maggie said with pride, unexpectedly grateful to be able to make this announcement. "I'm to take care of babies for a daycare center."

"There's always babies."

"That's what my father said."

The woman looked up sharply from the rose, her eyes hidden behind the reflection of the florescent bulbs against her glasses. "I thought I made it clear we're not big on fathers around here."

Startled, Maggie quickly apologized. She had paid too little attention and missed the household rule. She searched for a place to begin again, to indicate that she had accepted the reproof without offense. "I met the director, who introduced me to the other women." The administrator of the large church that housed the daycare had valued that she dressed plainly, listened attentively, and spoke rarely, as her father informed her on their drive home. The director cared, too, that the timing of her father's inquiry to a fellow government employee came the day after the old woman who had previously been caring for the babies was buried, with a substitute hired only for the week. This much Maggie gathered from the director herself, who wore pink lipstick and high heels and gave her a tour of the dusty old building, with its stone arches, tall windows covered in red velvet curtains, and a worn grand piano that anyone could play, things Maggie tried to describe to the fat lady now. The church, she said, offered ministries to the poor and a senior center and a daycare, with one small room on the second floor that was to be Maggie's, where a single bed covered with a quilt was pushed against a wall next to a nightstand. Maggie would share the bathroom down the hall with other female live-in staff, working in exchange for meals and an allowance. What Maggie did not say was that in the dining room where she had shared lunch with the staff, she could see that the other employees were skeptical of her. The women who took care of housekeeping and food service and the senior center were all gleaned from the church's rescue mission. Their hands were rough from the chlorine they used to clean with and their gums were dark and receding from tobacco. When Maggie entered the room, they looked pointedly away. She had approached the fold-out tables with an odd measure of comfort—if she were beneath their notice, she could get her bearings slowly.

The director, however, would not allow this lapse in attention to occur for long. She smiled at Maggie, indicating with a nod that she should wait, then listened for the first crack in the conversational barricade that the other women were creating. Someone said, "Well, they could have washed the pots out, anyway," to which no one had a quick enough reply. There was a dry cough and the director spoke.

"Ladies, we should say hello to Margaret, the newest member of our staff."

They all turned to look at her as if they had not seen her arrive. The look was brief and flat and then they turned again toward their food.

"Young, ain't she?" one woman said without taking a second look, dipping a spoon into her soup with chapped red hands.

The director seemed prepared for this. She balanced her pointy chin in the heel of one hand and stared at Maggie as if she might change her mind about giving her the job. "Yes, she certainly is that," she said after a moment.

"And isn't it too soon?" one of the women who cared for the toddlers said hesitantly. "Too soon for a replacement?"

In the silence that followed, they all considered their deceased friend.

"Well, someone's got to take care of the babies, for heaven's sake," the woman next to Maggie finally said without looking up from the bread she was buttering. "No reason to get sentimental about the job."

Maggie understood that the women were imagining how quickly the work they did could be given over to someone else in the face of death or illness. They worked so hard at their tasks that it seemed no one else could do them quite as well, and yet the work needed to be done all over again as soon as it had been completed. If they left or died, someone would have to be hired right away. There would not be time for others to notice the work being undone and to miss their doing of it. Maggie saw that they felt hard toward her because she reminded them of what would happen to them all. Overwhelmed with their bitterness, she did not look down at her soft young hands and she did not smile excessively, which was how the director had no doubt eventually won them over. Instead she just looked directly at whomever was speaking, thinking that she had never been in a room full of strangers and that she could barely breathe beneath the weight of all their feelings.

"Be having a baby herself before we even get her broke in," the first woman said, and scooted back her metal folding chair.

"Hush now," the director said gently. "She's helped birth and raise eight siblings out in the country. I think she knows a little something about babies," and here she turned and let her gaze linger on Maggie, "and that includes how not to have one herself."

This last comment had reassured Maggie that she and the director would have some point of agreement. The church formed an entire world that she would rarely need to leave, something Maggie understood.

"I'm to start on Friday," Maggie now said to the fat lady, though with the dreamy sweetness of the cupcake, she felt as if she might never have to go anywhere again at all.

"Good—no reason to be slow about it," the woman said in a congenial tone. "I've been trying to leave this place for years, and yet I rarely get beyond the front door. Going must be done quick and clean." She eased up on the last flower. "That is, if it's to be done at all." She looked at Maggie and gave a half smile. "Which reminds me. You'll need to head on now."

"Your cake looks lovely," Maggie said, sliding off the stool. "Do you sell them?"

"I used to deliver them to the grocer in town," the woman said, turning to the sink to rinse her hands. "Before my ex-husband's reputation ruined that for good. Now I sell them only sometimes, to some people. I give them to the man," she pointed toward the ceiling with one dripping wet finger, "sometimes just to eat, and sometimes to sell for supplies." Drying her hands on a towel, she said, "You'll see yourself out now."

Maggie thanked her for the cupcake and at the top of the stairs turned left instead of right, circling back in the direction that the prowling man had come earlier. Against one wall a fireplace loomed cold and unused, the heat for the house now coming from wide vents in the floor. The carpet here was also thick and mislaid, with only a few scattered pieces of furniture in the second of the two rooms—an armchair and a lawn chair and a tall wooden table lamp sitting on the floor next to a television. Maggie pictured her sisters crowded in front of the cartoons that the town kids who had televisions talked about, giggling over the funny parts, eating pink frosting roses from wax paper. Unsure whether she was relying on memory or imagination, she could envision her younger self here, too, relieved to have escaped from her brothers and from the baby girls, glad to be talking to the fat lady about the book that she was reading, though the fat lady hadn't much cared for books even then, believing that they just created expectations for life that could not be fulfilled. Yet while Maggie did not readily recall her own memories, which were dependent upon material objects to help them take shape, she could easily conjure the stories of others learned during her lessons long ago—the great scope of histories, snippets of anecdote from inventions in science, every detail of a reread novel. The rest of her hours had been occupied by chores that did not require language for execution and that did not benefit from the dramatic possibility that story inspired. She was bound by the senses, and other skills had grown dull.

Maggie heard a chair scrape upstairs, urging her to leave. On the front lawn, stopping to allow her eyes to adjust to the dark, she turned toward the illuminated dormer window of the second floor. There the silhouette of the man stared out, pipe in his mouth, scratching his chin. Hovering in the shadows that shielded her from his view, Maggie believed that she herself must have once sat in that very window, on perhaps the only occasion she had been allowed to spend the night with the fat lady's daughter, who liked to play records and who lived in a heap of her own things, scattered and folded and crumpled in piles around the bed. But the daughter was several years older than Maggie, and so she slept the sleep of the dead as a teenager should, hours into the morning when Maggie wasn't sure whether it was polite to leave without a goodbye, whether the stairs would be properly positioned for her to descend, or whether their brooding father would be wandering around in the front yard as he sometimes did, taking a break from his work in the shop. Paralyzed by these uncertainties as well as the used, store-bought sanitary napkin that upon waking she had spotted on the floor, Maggie stared out the window in the direction of her house, hidden behind the cane, unsure whether it was better to be at one place or the other.

The man disappeared from the window just before Maggie turned toward home. Leaving the yard she passed a rotting woodpile, where she saw a glint of fuchsia and leaned forward to investigate. A whole pile of broken glass glinted in the light from upstairs—emerald, indigo, sapphire, champagne, and rose-colored shards that in some places were still held together by a thin silver-gray thread of solder. She thought again of her brief memory of the basement earlier, glittering with jewels like a dragon's hoard before being turned into a gleaming kitchen, some transformation that must have occurred after the fat lady parted ways with her husband. Afraid to linger in case the prowling man came outside, Maggie walked down the hill and crossed the creek by the rocks.

By the light of the moon Maggie climbed back over the split rail fence of her own property. From here she could see that her house was dark except for reading lamps, but by the time she cut through the meadow and opened the back door into the kitchen, everything had gone black, the downstairs windows covered in curtains that her mother shut ritualistically at the finish of each day. In the kitchen, Maggie stopped to let her eyes adjust and to listen. She took account of the state of the house, of how it had fared in her absence and in what ways it would now try to draw her in or push her out. She heard only her brother Warren clearing his throat on the other side of the pantry wall, not waiting for her, not curious about when she might return or where she had been, but simply doing what he always did. Yet she knew before she reached the first step that she would be sleeping on the landing like a sailor on watch over a calm sea, witnessing nothing, making sure nothing continued to occur. But something had already happened down beneath the depths that had only just this morning rippled to the surface, the tip of a fin that was her declaration to leave, and the whole huge leviathan would soon cause the entire ocean to heave.