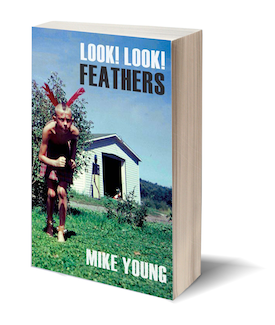

Look! Look! FeathersBy Mike YoungWord Riot |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Barry Graham

If Mike Young told me he grew up in a suburban castle full of lawyers and lion tamers and medicine men, or that he was raised on the edge of the ocean, the adopted son of a snake charmer father and truck-driving mother whose real parents escaped a cult and left him on the front porch of an orphanage, I would believe him. If he told me he grew up the son of uneducated peasants who drank and gambled and whipped their pets and their children equally, I would believe that too. That how's convincing his prose is. Young writes with authority. His voice and his words and his sentences feel earned, authentic. It feels like this:

Outside, ladies walk dogs dressed in miniature ponchos. The rain falls and falls. We pass a schoolyard, its jungle gym and hobbyhorse all soaked and abandoned. When we pass other cars, our tires and their tires swap raspberries of street water. Rain is made of water and blame. Okay. You've seen rain before. Let's not get carried away. We can see the pitch of things just fine .

Look! Look! Feathers is a collection of twelve stories as odd and mysterious and elusive as the memories we carry with us from childhood into adulthood, and for me, that's where the primary concern of this collection lies. Young's characters yearn for childhood, for a time less occupied with jobs and worries and responsibilities, a time, perhaps, when your brother was your only friend and life was much, much simpler because you didn't stop to think about what it would all mean later, a time when dreams were still easy to believe in, when the idea of being a basketball star or even a firecracker seemed magical and far-fetched, but still possible.

In the opening story, "The Peaches Are Crisp," two brothers share a car ride home from work. The younger brother struggles to connect with his brother the way they did when they were kids. After some small talk, this happens:

"I want to turn into a firecracker," I say.

He spits. "I want to turn into a basketball star."

It's one of our tired little games.

"Let's learn to drive steamships," I say.

He kind of smiles.

We go to the supermarket and buy canned peaches. The cashier squints at my brother. He winks and steals a penny from the charity saucer. Out in the parking lot, we eat the peaches with our car doors open.

Then this:

We used to shove each other off of rope swings. We used to shove each other off of fire escapes. Now I work for the gas company. He works at the post office. I nod.

Sometimes, under this drawl of light, a dying will find your jaw. There are old fences and old dogs all over this town. By September, my brother will be seeing the supermarket teller and scoring free beer.

I drop him off at his place. Before he leaves, he leans into my window for a long time, then he thanks me for the ride. I think to ask him about playing pool, about buying a pizza.

Instead, I say, "Tomorrow, right? Like Batman. Same time, same channel."

It's obvious the brother wants to reach out. The reader is never told why he doesn't. Is it fear of rejection? Is it knowing that things have changed and will never be as they once were? We can only guess. That is one of Young's tricks, one he's mastered. He unapologetically forces the reader to do some guesswork, to superimpose themselves into the story and live it and experience it right along with the characters. It's one of Young's many charms. The tale comes to a seemingly violent end:

I drive home with my eyes open, then I drive with them closed, hoping to hit something, anything, like a refrigerator box, or a wall of lightning bugs, or a kid on his bicycle, the only thing he really loves.

At first this seems sadistic, a needlessly bloody end to an otherwise routine car ride home. Until we do what Young asks of us as readers and join him in the car: then, at least for me, it becomes something different, it becomes a young man searching for a way to start over, to relive the good and change the future before it gets to where it ends up. Before death sounds like a good option. And for me, the best of the stories in this collection feel this way. Not quite a cry for help, but a wish that can't come true, the ability to go back in time and do things right the first time.

This continues in "Burk's Nub," where we experience the cruelty of one band geek picking on another. Instead of camaraderie, there is tension: the narrator feels disgust for Burk's size and smell and broken home, but the narrator is also jealous because Burk doesn't seem to mind it all. He can still force a smile, take his shirt off, and let his gut hang out:

I followed him into his parking lot. His apartment complex was short and squat, yellow as fake cheese. Doors and windows spaced in uniform. It looked like a row of cubbyholes, the pattern only broken by things beside the doors: someone's pink stroller, a black trash bag. Inside, it stank. As soon as it hit me, I tried not to notice. Actually, first I tried not to breathe, and then I tried not to notice. Old carpet, sweat, and roach spray all congealed into this weird, moist odor. Sure enough, Burk tossed his backpack and swiped off his shirt. He chucked it into a pile of similar shirts beside a television. His gut jiggled as he walked down a hallway. My imagination crossed its arms and nodded: yep, Jabba the Hut. I felt like a bastard.

And again with "What the Fuck Is An Electrolyte." A meager, disappointing childhood turns into an an even more disappointing adulthood that leaves both the reader and the characters who were forced to endure the circumstances, begging for a do-over, for one more chance to get it right, for the magic of the butterfly effect. Failed musicians turned cannery workers. Even when a little hope is found, as with Monty joining a band, you wonder if he wasn't better off staying with his mom and working the 9-5:

Monty knew that nobody would notice him. Not until somebody flipped out and he had to collar them. Fuck this shit, they'd bellow. And Monty knew of the shit they meant, he understood why they were always trying to fuck that shit, but all they ever did was fuck themselves. Shit, meanwhile, kept thumping away, pervasive as the bass that people—who called and complained—could hear for miles. But nobody—not the cocksuckers in the casino, not the squares dinking around in the foothills—would care about his wet ass. Why should they? Who did anything worth caring about? People hawked their drums. They wore orange headphones. Purple sweatpants. They played text-based RPGs. They mopped naked. Without permission or proof, they accused others of luck. They sought electrolytes as welts glittered and roaches crawled from milk.

In the title story, "Look! Look! Feathers," we find another first-person narrator good at describing everyone and everything except for himself. Although he often gives us access inside his narrators' heads, Young rarely does it in order to give us insight into how they themselves are thinking and feeling. It is mostly always to tell us about something or someone else. This may stem from the narrators not knowing or understanding their own identities except in relation to their environments and the company they keep, as in "Burk's Nub" and "Look! Look! Feathers" and another story, "Susan White and the Summer of the Gameshow," where a community evaluates itself from the inside out with the help of an outside orchestrator and discovers how much and how little they truly know about one another.

As flawed as Young's characters are, he never judges them, never treats them with scorn or revulsion. He doesn't make excuses for them, either. He just narrates, reports to the reader what he sees, and lets us decide for ourselves who to root for.

Look! Look! Feathers is a collection that will mean something different to each reader. Who we like and dislike, who we think deserves redemption, compassion, mercy, tragedy, cruelty, love, and success, all of that will depend on who we are as people, on the lives we have lived and the morals, values, beliefs, biases, and life experiences we bring to the table before even opening the cover. In Look! Look! Feathers, Young transcends storytelling. He is a Puppetmaster.