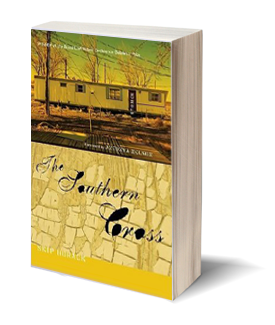

The Southern CrossBy Skip Horack |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Stacy Muszynski

The sixteen stories that form Skip Horack’s Bakeless prize-winning debut collection, The Southern Cross, are tough and lean and proud as the Southern Gulf Coast characters who fill their pages. With restraint, empathy, and an intimate understanding of dramatic tragedy, each piece steadily and surely cuts to the blood-bright bone.

They must: Horack’s premise, “the solemnity of the remorseless working of things,” necessitates that every story concern itself with death. But Horack goes further. His stories begin already in the process of mourning, fully aware that life itself is suffering.

“Borderlands,” for example, the twelfth piece of the collection and one of its four longest at nineteen pages, opens with these lines:

His setter found her in a cold canebrake, half-buried in the loam, her mouth sealed with duct tape. Wes saw it was her, Sara Champagne. Three fingers had been cut from her right hand, two from her left. She was naked to the waist, and a thin red tear ran from the base of her throat and then down across her belly.

The story is as much about a Louisiana teenager’s hair-trigger murder of a murderer, as it is about the heart’s vagaries and tender spots. Like the stories it rubs against, “Borderlands” is a meditation on innocence already destroyed and the perils still faced by life left in that wake. It shows Horack’s acute care of narrative structure as well, how his sharp tools disappear borders between emotion, action, history and place. Here’s one example—a scene between Wes (the boy who’s discovered Sara Champagne’s body and killed her murderer) and his uncle, a local cop :

“That man never came at me or nothing. He just smiled, and I was so scared I shot him.”

Cameaux lifted an eel-slick catfish by the mouth, then pushed its bottom lip through the timber tie. […] “In the war I saw things, did things, that I never thought I’d shake.”

“That’s kinda how I feel about this,” said Wes. “Like I ain’t never been so scared.”

Comeaux […] made two shallow cuts, one on either side of the catfish’s dorsal fin. “You know, I spent a few months in Korea between tours. […] An Eden really. […] The say it’s still that way.” Comeaux plier-peeled great strips of gray skin from the impaled catfish. “There’s peace to be found in this world, Wes. You just have to look.”

The channel cat hung naked on the nail, gills still working steadily as Comeaux began to cut out the fillets. Wes watched it suffer and bleed. “I guess,” he said.

Caught in the cross-current of abundant beauty and violence, Horack’s people, neither martyrs nor sentimentalists, whose own pain is as old and Bible-drenched as Eden, seek their peace. They’re connected by time—that fateful year of seasons in 1995. They share a “tangled delta of channels,” as one of his characters puts it in “The Final Connor.” Beyond waterways The Southern Cross makes clear that connections are made by history, bloodline, barter, sex, flight and fight, marriage, fantasy, murder, even simple religious iconography worn on a chain that swings between bodies making love or else glints in the headlights of an eighteen-wheeler at dusk. All crosses take risk, and most risks, it seems, are attempted for some form of freedom.

These characters share sensibilities, old and deep, as well as a detached response to inherently hostile forces that dominate their lives: War, weather, human frailty and imperfection, all parts of a game they cannot win. They share loss, and yet they are endowed with their creator’s spirit, intellect, and sly sense of irony, a sass and grit that surprises themselves and readers. The title character of “Junebelle,” for example, as old as she is wise and lonely, says, “Truth is, I don’t believe in God anymore, Catholic or otherwise, I just woke up one day and stopped. […] I thought I’d be sad, but to be honest, it felt delicious. Like that was the last decision I had left that I could make for myself. Who knows? Maybe tomorrow I’ll go back to believing.”

Horack’s own faith is in his characters’ power to make decisions and act on impulses despite all their natural disasters, fallen relationships, and fucked-up lives. It has to do with their senses of observation and humor in the face of life’s pain. He shows us both in “The High Place I Go”:

What’s plain old Saturday evening to you and me is Steak Night to the folks at the Carousel Bar and Grill. A teenage waitress shows us to our table, just a couple of steps from this little circular stage that’s revolving three-sixty, spinning round so slow that I barely notice it moving. No band’s in sight—thank God—but there’s a card table set up on the stage. Four men are playing what looks to be poker, that all-in hold’em you see on TV. They sit still as statues, their faces hidden behind wrap-around sunglasses and these veils of camouflage mesh.

What are these veils? “Facemasks. To keep from giving away their tells.”

We recognize that protective gear. Hell, we wear it too.

In “Caught Fox,” Horack gives us the story of Lucas Benton, a screw-up ex-husband and father whose constant innuendo, double-entendres, and grabbin’-ass of an 18-year-old add juice to the story and heartbreaking echo effects. By working his voodoo surgery on emotion, action, history and place—all this in piece’s opening paragraph—Horack opens Benton’s wounds. Out spills sexual frustration, his longing for the glory days, that Southern politeness to strangers, and his beleaguered hope for miracles despite his cynicism:

I’m rounding the bend at Johnson’s Corner when I see Reverend Lyle has a girl waist deep in a concrete pool behind the church. He pauses the ritual and nods my way as I pass. His little brother Melrose was my split end back in the day, caught half the passes that set me up all-district. That still counts for something, so I lay off the gas to keep the dust down on the gravel road—away from the black women and their Easter hats. Maybe even give that shivering child’s brand-new soul a shot at staying shiny and clean.

Life is suffering but we hope for relief, and so we forgive then appreciate every crude joke, each and every bit of sexual innuendo and double-meaning Benton throws at us throughout the story. And we cheer again when, in the next story of the collection, “Chores,” we see the Bethel Baptist roadside sign: “OUR CHURCH IS PRAYER CONDITIONED, PLEASE COME PRAY WITH US.” It’s a small joke but a winning one, and well-timed.

Look, you won’t find Horack’s people in church. They find other places to work out their pain. Most head out of doors entirely, and all end their stories face-to-face with the most remorseless elements of their lives. It’s how they earn that delicious bit of freedom.

Better for us that each character’s journey borders on epic and their tracks are evident. Even if as the narrator of “Bluebonnet Swamp” tells us, some of these tracks “cannot be explained.”

It’s not story’s job to explain. Instead The Southern Cross offers us sixteen whole, new worlds. It makes it easy to follow Horack’s unnamed lawyer, cross his Baton Rouge street, climb that briar-choked fence, and head into “Bluebonnet Swamp.” We won’t turn back when he tentatively descends into the mud cave hidden inside his city, inside his own neighborhood. He won’t invite us, but we’ll be there noting how his body shifts in the shadows, how his shoulders relax into his new peace. We’ll be so close it’ll be our voice we hear say, “[T]hough it is dark at first, a few steps more and he can't believe what he is seeing, what he has been missing this whole time, these worlds within worlds.”

And we’ll get that the final “cross” of The Southern Cross is a double-cross by Horack himself: in his sixteen meditations on dramatic tragedy, no corpse is carried out in the end. In a world infused with violence and uncertainty the heroes here live on. And with a measure of freedom, even with all its costs, despite all the long odds.